| |

June/July

2015

- Volume 9, Issue 3

Medical-Surgical Nurses' Experiences of Calling a Rapid Response

Team in a Hospital Setting: A Literature Review

|

( (

|

Badryah

Alshehri (1)

Anna Klarare Ljungberg (2)

Anders Rüter (3)

(1) Badryah Alshehri,

RN, BCN, Critical Care Nurse,

Sophiahemmet University, Stockholm, Sweden.

(2) (Mrs Klarare);

Anna Klarare Ljungberg: RN,MSN ,PhD,

Sophiahemmet University. Stockholm, Sweden.

(3) (Mr Rüter); Anders Rüter: MD,

Associate Professor of Surgery particular disaster medicine.

Stockholm, Sweden

Correspondence:

Badryah Alshehri,

BSN, RN, Sophiahemmet University , Spanga, 16368, Hyppingeplan16,

Stockholm, Sweden

Mobile phone: + 46765505100

Email: baa325@gmail.com

|

|

|

Abstract

Background: The rapid response team (RRT) decreases

rates of mortality and morbidity in hospital and decreases

the number of patient readmissions to the intensive

care unit. This team helps patients before they have

any signs of deterioration related to cardiac

or pulmonary arrest. The aim of the RRT is to accelerate

recognition and treatment of a critically ill patient.

In addition, in order to be ready to spring into action

without delay, the RRT must be on site and accessible,

with good skills and training for emergency cases. It

has been reported that many hospitals are familiar with

the concept of RRTs. There is a difference between this

team and a cardiac arrest team, since the RRT intervenes

before a patient experiences cardiac or respiratory

arrest.

Aim: To describe current

knowledge about medical-surgical nurses' experiences

when they call an RRT to save patients' lives.

Method: The method used

by the author was a literature review. The PubMed search

database was used and 15 articles were selected, all

of which were primary academic studies. Articles were

analysed and classified according to specified guidelines;

only articles of grades I and II were included.

Results: Years of experience

and qualifications characterise the ability of a medical-surgical

nurse to decide whether or not to call the RRT. Knowledge

and skills are also important; some hospitals provide

education about RRTs, while others do not. Teamwork

between bedside nurses and RRTs is effective in ensuring

quality care. There are some challenges that might affect

the outcome of patient care: The method of communication

is particularly important in highlighting what nurses

need RRTS to do in order to have fast intervention.

Conclusion: Medical-surgical

nurses call RRTs to help save patients' lives, and depend

on their experience when they call RRTs. Both medical-surgical

nurses and RRTs need to collaborate during the delivery

of care to the patient. Good knowledge and communication

skills are important in delivering fast intervention

to a critically ill patient, so that deteriorating clinical

signs requiring intervention can be identified.

Key words: Medical-surgical

nurse, rapid response team, experiences, challenges,

hospital.

|

Introduction

There are some hospitals that apply plans to prevent

mortality and morbidity for patients who are critically ill,

by using guidelines to protect patients when a staff nurse

notices signs of instability before undergoing cardiac arrest

(Chan, Jain, Nallmothu, Berg, & Sasson, 2010; Butner,

2011). A nurse who is assigned

to a critically ill patient will have the chance to help the

patient to survive. Not all nurses expect that their patient

is experiencing an arrest (Dwyer & Mosel, 2002). However,

many studies have reported that the hospital staff's failure

to recognise the early signs of deterioration in patients,

such as decreasing systolic pressure and abnormal breathing,

can lead to serious concerns, such as some cases like post

surgical infection, cardiac arrest code and even death (Abella

et al, 2005; Peberdy et al., 2003).

A patient has the right to receive

good quality of care (Burkhardt & Nathaniel, 2008). Good

quality of care means improving the available health services

for individuals to achieve their desired outcomes (Vincent,

2010). Furthermore, good quality of care, from a hospital

administration's point of view, means the prevention of illness,

infection, and decreases the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) re-admissions.

It has been suggested that, in order to improve patient outcomes,

surveillance to identify problems should be linked to effective

responses (Green & Allison, 2006). To tackle this issue,

a system termed 'the Rapid Response Team' has been initiated

(Institute for Health Improvement [IHI], 2013). The Rapid

Response Team helps to decrease mortality and morbidity rates,

and also allows nurses to intervene when a patient has signs

of deterioration before they experience a cardiopulmonary

arrest (Jenkins & Lindsey, 2010).

Background

Around 60 per cent of hospitals in the US have experiences

with patients who undergo cardiopulmonary arrest (Winter et

al., 2007). Other studiesy show that most of the clinical

deterioration signs for patients are exhibited before they

reach cardiopulmonary arrest (Azzopardi, Kinney, Moulden &

Tibballs, 2011). Health care professionals have a responsibility

to know the signs of deterioration for critically ill patients

and to have responses to prevent it. Not all professional

health care workers recognise the signs that lead to death

(National Patient Safety Agency, 2007; National Confidential

Enquiry into Patient Outcome And Death, 2005). There are some

challenges that hospitals face, such as managing healthcare

workers and providing available resources, in achieving and

managing patient care and outcomes of patient services

(Rogers et al , 2004).

The Institute of Healthcare Improvement

([IHI], 2013) established in 1980 by Dr Don Berwick, works

with a group of committed individuals to re-design healthcare

into a system without delay, time consuming tasks, errors

and unsustainable costs. The IHI focuses on key aspects, including

person- and family-centred care, improvement capability, patient

safety, and quality, cost and value. The goal of the IHI is

to improve the lives of the patients and health communication.

They concentrate on safety, effectiveness, time lines, efficiency,

and equity.

Rapid Response Team: Strategies

for Saving Lives

The Institute of Health Care Improvement (2001) undertook

the initiative of the 100,000 Lives Campaign in 2004, intended

to reduce mortality and morbidity rates. This initiative's

strategyies is to implement the best practice and also to

prevent pressure ulcers, reduce methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus (MRSA) infection through control processes and policy,

reduce infection through basic changes in infection control

processes, reduce surgical complications by implementing changes

in care, and prevent harm caused by high-alert medications,

beginning with a focus on anticoagulants, sedatives, narcotics

and insulin. They achieved this goal, partly by recommending

the implementation of a Rapid Response Team (RRT).

The goal of this campaign was to save 100,000 lives during

the time from its launch in December 2004 until June 2006.

Since then they have launched a successor, the Save 5 Million

Lives Campaign. In December 2006, the Institute of Healthcare

Improvement recommended implementing the RRT as one of six

strategies used to identify patients who were experiencing

pre-arrest in unplanned ICU admission. The strategies behind

the implementation of the RRT were to bring ICU-level patient

care to the bedside of critically ill patients, to work together,

and to assess and intervene in order to save patients' lives

(Institute of Healthcare Improvement, 2013).

Currently, more than 25 per cent of US hospitals use RRTs

to decrease the incidence of cardiopulmonary arrest, re-admissions

to the ICU and deaths by providing early intervention for

patients whose conditions are acute and progressively deteriorating

(Donaldson, Shapiro, & Scott, 2009).

Different Terms for the Rapid

Response Team

It is important to understand the terminology of the Rapid

Response Teams. In the past, they were called Medical Emergency

Teams (METs) or Medical Emergency Response Teams (MERT), and

other terms including Patient at Risk Team (PART) and Critical

Care Outreach Team (CCOT) have also been used. Some of these

terms are interchangeable in places such as Australia, where

RRT and MET have the same meaning (DeVita, Hillman, &

Bellomo, 2011).

The similarity between the RRT and

the MET is that they help critically ill patients from the

emergence of any signs that could lead to cardiac or respiratory

arrest. Both maintain the two key features of an afferent

limb, such as how the team is activated, and an efferent limb,

such as the response of the team. There are, however, some

differences between them: RRT is generally used to mean a

nurse-led team, and the MET is generally a physician-led team.

In this thesis, the author will use the term 'Rapid Response

Team' to cover all of these terms, as it is the most commonly

used variant in the literature (DeVita, Bellomo, Hillman,

et al, 2006).

Definition of the Rapid Response

Team and its Purpose

DeVita et al. (2011) defined a Rapid Response Team (RRT) as

a group of healthcare professionals who are trained for critical

cases and deliver quick critical care. A RRT's members come

from multiple disciplines, including an intensivist, a physician's

assistant, a critical care nurse and a respiratory therapist.

The purpose of this team is to be

ready to spring into action without delay, and they must be

onsite and accessible;, they must have good skills and be

trained well for emergency cases (Moldenhaure, Sabel, Chu,

& Mehller, 2009).

An RRT is able to respond rapidly to a deteriorating patient

with an average response time of less than five minutes (range:

2-10 minutes), and the duration of RRT calls averages between

20 and 35 minutes (range: 5-98 minutes). A RRT is intended

to prevent hospital deaths caused by medical error in medical-surgical

wards or wherever they occur, such as in an intensive care

units (Hatler et al., 2009; Chamberlain & Donley, 2008).

Hospital Mortality and Morbidity

Numerous studies have shown the numbers of patient lives saved

when RRTs have been activated. A study in one hospital indicated

that the RRT was called 344 times over a period of 18 months.

The same study reported 7.6 cardiac arrests per 1,000 discharges

each month over a five-month period before the RRT was implemented.

However, with the introduction of the RRT, the number of cardiac

arrests over a 13-month period subsequently decreased to three

episodes of cardiac arrest per 1,000 discharges each month.

Prior to the implementation of the RRT, the mortality rate

was 2.82 per cent; after the RRT implementation, it decreased

to 2.35 per cent. Additionally, the percentage of ICU re-admissions

decreased from 45 per cent to 29 per cent (Dacey et al., 2007).

According to Bellomo et al. (2004),

the implementation of RRTs reduced adverse events in postoperative

patients, such as severe sepsis, respiratory failure, stroke,

and acute renal failure. It also reduced the duration of hospital

stays. There were 1,369 operations for 1,116 patients during

the control period and 1,313 for 1,067 patients after the

intervention of the rapid response team (RRT). The result

was a decrease in the rate of respiratory failure incidents

to 57 per cent, while the relative stroke risk reduction was

78 per cent; severe sepsis had a relative reduction of 74.3

per cent; acute renal failure requiring renal replacement

therapy relative reduction had a relative reduction of 88.5

per cent; and emergency intensive care admissions were reduced

to 66.4 per cent. Furthermore, the rate of postoperative death

dropped to 36.6 per cent, and the average duration of hospital

stays decreased from 23.8 days to 19.8 days.

DeVita et al. (2006)'s findings supported

the conclusion that the use of RRTs indeed decreases adverse

outcomes and unplanned ICU admissions, and stated that hospitals

should implement RRTs.

A recent study compared mortality

rates before and after the implementation of RRTs. It was

indicated that the initial mortality rate was 22.5 individuals

per 1,000 hospital admissions. After the RRTs were implemented,

the mortality rate dropped to 20.2 per 1,000 hospital admissions.

The utilisation of RRTs decreased the mortality rate, as well

as decreased ICU re-admission (Alqahtani et al., 2013).

Another hospital indicated that

the number of cardiopulmonary arrests before implementing

a RRT was 75 per 1,000 admissions in 2006; after implementing

the RRT, the number of cardiopulmonary arrests decreased from

59 to 37 per 1,000 admissions during 2007 and 2008 (Hijazi,

Sinno, & Alansar, 2012).

Another study found that, from 378 calls for a RRT during

a time period spanning from 9 months before until 27 months

after implementing a RRT, cardiac arrests were reduced by

57 percent, amounting to a reduction of 5.6 cardiac arrests

per 1000 hospital discharges. Around 51 arrests were prevented

(Geoffrey, Parast, Rapoport, & Wagner, 2010).

Konrad et al. (2009) found that, in a hospital where the number

of RRT calls was 9.3 per 1,000 hospital admissions, the MET

implementation was associated with a 10 per cent reduction

in total hospital mortality. The number of cardiac arrests

per 1,000 admissions decreased from 1.12 to 0.83; mortality

was also reduced for medical patients by 12 per cent, and

for surgical patients not operated upon by 28 per cent. The

30-day mortality pre-MET was 25 per cent versus 7.9 per cent

following the MET implementation compared with historical

controls. Similarly, the 180-day mortality was 37.5 per cent

versus 15.8 per cent, respectively.

The study by Scott and Elliot (2009)

showed that before implementing RRTs, 22 cardiac codes were

called per month. After implementing RRTs, this number decreased

to 14 per month. Before the implementation, the cardiac codes

were mostly called for patients who required intubation; afterwards,

the cardiac codes were seldom used for intubated patients

because the RRT had been called before the patient's condition

deteriorated.

The Criteria for and Purpose of

Calling RRTs

When the medical-surgical nurse calls the RRT, there are certain

criteria involved in the decision. When a medical-surgical

nurse notices that their patient is almost at the point of

requiring intervention, the staff nurse will review the criteria

to assess a patient before calling the RRT. Each hospital

must use certain criteria when it comes to calling RRT. The

following will help to determine who should call RRT; using

the proper protocol will help to reduce the incidence of mortality

and morbidity due to unexpected cardiac arrests in the hospital

(Buist, 2002). A study found that, through implementing RRTs,

the number of calls for RRTs increased through an understanding

of their outcome in saving patients' lives (Hillman, et al.,

2005).

Each member of the team has a role to play during an intervention.

The role of the RRT nurses is to assist the bedside nurses

and to assess patients alongside them. The role of the physician

is to assess the patient, evaluate the clinical findings in

relation to the patient's history, and to determine the appropriate

intervention with the other team members. Calling the RRT

is commonly done for surgical patients, emergency department

patients, elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, and

critically ill patients with a longer length of stay at the

hospital (Young, Donald, Parr, & Hillman, 2008). The criteria

that a nurse in a medical or surgical ward should follow in

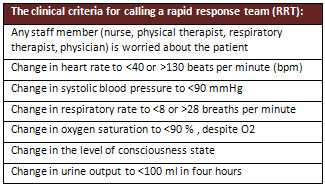

deciding whether to call an RRT are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: The clinical criteria

for calling a RRT

(Institute of Health Care Improvement,

2011)

The impact of implementing a RRT

is to maximise the climate of safety for a medical-surgical

patient. Promoting a more cohesive clinical approach hospital-wide,

such teams augment expertise and communication with the skills

of the nurses throughout the facility (Sharek et al., 2007).

Process for Calling a Rapid Response Team

Each hospital uses a framework for RRTs, with plans and the

mechanisms in place for a deteriorating patient. When a nurse

notices that a patient's condition is declining, after applying

the criteria, the nurse will call the RRT by pager or telephone

extension per the hospital's protocol (Institute for Clinical

System Improvement, [ICSI], 2013). The nurse will then give

a verbal report of relevant information using the communication

tool of SBAR: 'Situation' refers to the room, the ward

and a brief about the patient, including the name, age, admission

date and the reasons for admission; 'Background' covers

information about the patient's history and conditions, a

list of medications, lab results and other clinical information;

'Assessment' is the nurse's assessment of the situation;

and 'Recommendation' is what the nurse recommends,

such as whether a patient needs to be seen immediately or

needs an X-ray (Ray et al., 2009; Cretikos et al., 2006).

According to the Institute of Health

Care Improvement (2013), SBAR is an easy and effective tool

for communication about a patient between staff members.

Definition of Nursing and Nurses'

Responsibilities

Nursing is defined as protecting, promoting and optimising

health care while preventing illness and alleviating suffering

through diagnosis and treatment. Nursing is primarily concerned

with providing care to the physically ill, mentally ill and

disabled. Nursing includes collaborative care for individuals

of all ages, regardless of family, group or community, sick

or well, in all settings (International Council of Nurses,

2012).

Nurses are responsible for patient care, where each nurse

is accountable for his or her individual nursing practice,

performing assigned tasks and providing optimum care. In all

their other responsibilities, such as administration, teaching

and research, each nurse is responsible for the quality of

practice within their standard of care (American Nurse Association,

2011).

Nurses' Experience and Practice

Nurses' experience can be defined as their acquisition of

knowledge and skills from feeling, seeing and doing. Another

definition of nurses' experience is the achievement of a high

level of knowledge, work and experience relating to healthcare

from mind-body practices. Nurses' levels of understanding

evolve through their experiences of practice in clinical settings

(Kemper et al., 2011). In practice, nursing requires special

skills and knowledge, as well as independent decision-making.

Nurses must deal with different settings, types of patients,

diseases and ways of giving treatment. Nurses protect those

who need care (National Council of State Boards of Nursing,

2013).

Medical-Surgical Nurses

Nurses who work in medical and surgical wards are registered

nurses who have been professionally registered after passing

an examination to have the licence certification in order

to be qualified to perform nursing care, as well as being

equipped with the skills required to assess patients physically.

Furthermore, they have the ability to make clinical decisions

about the appropriate treatment and nursing intervention for

a patient by performing an assessment, developing a plan of

care and predicting patient outcomes (Keller, Edstrom, Parker,

Gabriele, & Kriewald, 2012).

Problem Statement

It has been reported that many hospitals

are familiar with the concept of the Rapid Response Team.

The difference between the RRT and a cardiac arrest team is

that the RRT intervenes before a patient experiences cardiac

or respiratory arrest. The RRT is a system recommended by

the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI, 2010).

Significant evidence has shown that RRTs save patients' lives

by mitigating medical errors, decreasing ICU admissions, and

reducing the number of days spent in hospital (IHI, 2013).

Because of this, the author focuses on medical-surgical nurses

who are assigned to critically ill patients, who have complex

responsibilities, may struggle with lacking confidence, or

experience other challenges during RRT calls due to medical

errors. The author also seeks responses from bedside nurses

when they notice that their patient needs RRT intervention

(Thomas et al., 2007).

AIM

To describe the current knowledge

about medical-surgical nurses' experiences when they call

Rapid Response Teams to save patients' lives.

Research Questions

- How do nurses describe their experiences

of calling RRTs?

- What are the common challenges for nurses when calling RRTs?

METHOD

Study Design

A literature review is the gathering, analysis, and critical

summary of information for a particular topic of study. The

literature review is a helpful method for the researcher to

collect and condense information (Polit & Beck, 2012).

The fundamental aim of a literature review is to provide a

comprehensive picture of the existing knowledge relating to

a specific topic (Coughlan, Cronin, & Ryan, 2013). Moreover,

the use of this method helps to inspire and generate new ideas

by highlighting any inconsistencies in current knowledge,

from among studies published in some search database such

as PubMed, considered the most significant database in medicine,

and including the entire field. PubMed primarily accesses

the MEDLINE database, which includes references and abstracts.

PubMed also involves a full articles database from different

countries (Aveyard, 2010). In this study the PubMed database

was used to retrieve all articles. The vocabulary and terminology

used to search the PubMed database were found using MeSh (Medical

subject Headings), a dictionary used for indexing articles.

Data Collection

Data collection is a formal research procedure used to help

a researcher. This study performed a search to find articles

relevant to nurses' experiences during calls to RRTs. PubMed

is considered as the most significant database for this purpose

and has been used in this study (Polit & Beck, 2012).

All 15 articles retrieved from PubMed

answered the study's aim. MeSH terms were used to find some

of terminology, which was then used in a free search in PubMed.

However, there were no articles found in MeSh database related

to this topic (Polit & Beck, 2012). The terms used in

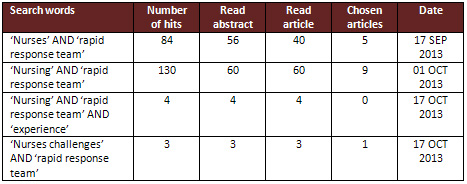

MeSh were: 'nursing' AND 'Rapid Response Team'; 'nurses' AND

'Rapid Response Team'; 'nursing' AND 'Rapid Response Team'

AND 'experience' and 'nurses'; and 'challenges' AND 'Rapid

Response Team' (see Table 2). The following inclusion and

exclusion criteria were applied during search in selecting

articles for this review.

Selection Criteria

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria was to include articles, then analyse

them for use in the result (Polit & Beck, 2012). This

criteria used for each article included had to be written

in English, with a publication date no earlier than ten years

ago, and also filed under publications involving the nursing

field. These were then used as the primary source texts, original

studies and primary sources.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria was to exclude articles not to be used

in the result, because they did not meet with criteria used

in research (Polit & Beck, 2012). The criteria for each

article excluded were those that were not written in English,

those that were not relevant to nurses' experience in calling

for RRTs, articles relating to the medical rather than nursing

area, and literature reviews about RRTs. Other excluded articles

were in report form and were not complete articles, while

other articles were more than ten years old.

Table 2: Searches in PubMed

Data Analysis

Data analysis is an organisation and synthesis for

a study (Polit & Beck, 2012). All 15 articles were read

several times and then analysed. Each article was analysed

separately and independently. The main findings were highlighted

in different colours and documented on a separate piece of

paper divided into two columns. The words describing nurse

experiences were highlighted in green and words relating to

challenges were highlighted in orange. This documentation

was written up using Microsoft Word under titles and a sub

title (Curtis, 2008). All of the articles were then evaluated

in order to check their validity and reliability by looking

at the qualifications of the authors and the study design

and process (Background, Aim, Method, Results, Discussion,

Ethical Considerations, and References), the number of participants

in each study and the environment. Then each article was graded

and classified using the guidelines for the quality of an

academic article. The grade scale used was: high (I), moderate

(II), or low (III) quality (see Appendix II).

Classification of Included Articles

The quality of each article and the types of methods used

were classified based on the criteria of Berg, Dencker, and

Skärsäter (1999) and Willman, Stoltz, and Bahtsevani

(2006), and modified by Sophiahemmet University (see Appendix

II). All the results relating to the article were collected

and were written into the matrix table (see Appendix I). Each

article used different methods ranging between qualitative

and quantitative methods. Some articles used interviews or

focus groups, some used descriptive correlational design,

some used qualitative ethnographic methods, and some provided

quantitative numerical data examining the implementation of

RRTs. Of the 15 articles used, there were 10 articles that

scored grade I and the remaining articles were grade II. In

addition, all articles were appraised according to the qualifications

of each researcher and whether there were any ethical considerations

noted, aiming to determine whether the research had received

support from any company, advertisement or commercial purpose.

All the articles were checked to see whether the researcher

considered the environment of the study when collecting the

data. Furthermore, the author checked to see if the topic

was appropriate to the aim of the study. (Polit & Beck,

2012).

Ethical Considerations

Permission to do this study was obtained from Sophiahemmet

University for thesis project of a bachelor degree. The author

dealt with each study using equitably all articles being read

and using all the results in this study, and used trustworthy

data collection, analysis and interpretation to avoid any

desired finding. Paraphrasing was done after the analysis

of all articles. There was no adding of any personal information

or comments to the articles, in the strictest effort to avoid

plagiarism, falsification and fabrication while conducting

data analysis. Each study was conducted in an ethical way

during data collection and interpretation. References for

each article have been stated in order to make it easy for

the reader to locate the necessary information (Polit &

Beck, 2012).

Results

The findings in this study were based on 15 articles. These

articles focussed on nurses' experiences and challenges in

calling RRTs. The results are presented in accordance with

the research questions.

Nurses Describe Their

Experiences of Calling RRTs

Nurses' Experiences and Qualifications

Most medical-surgical nurses were familiar with calling

an RRT as part of improving patient care. Calling RRTs has

increased nurses' experiences of preparedness. However, other

medical-surgical nurses had been hesitant to call RRTs because

the physician discouraged them to call. The decision to call

an RRT depended on the years of experience of ward nurses

when there was a critically ill patient requiring intervention

from an RRT. Nurses who had 0-5 years of experience were less

likely to call an RRT, while nurses with 11 years or more

of experience called RRTs without asking other nurses (charge

nurse) or the primary team. (Salamonson, Van-Heere, Everett,

& Davidson, 2006)

The qualifications of nurses relate

to their experiences when calling an RRT for an urgent case;

those with an associate's degree in nursing (AND; who study

nursing for two years) with less than or equal to three years

of experience called at the request of another nurse (i.e.

the nurse in charge) or a physician. Comparing this response

to that of staff nurses with a bachelor of science in nursing

(BSN), who have more than three years of experience and who

study nursing for four years; they called the RRT following

the criteria provided (Pussateri, Prior, & Kiely, 2011).

Some experienced ward nurses independently

called for a RRT without waiting for any decision from the

other nurses or physicians. The decision whether or not to

call a RRT was based on the nurses' judgment on whether immediate

assistance was needed. Some bedside nurses, who often ask

for advice and consult with other nurses when unsure about

whether or not to call a RRT, were encouraged to trust their

own judgment before calling RRTs, in order to get the support

and the affirmation that they needed (Wynn, Engelke, &

Swanson, 2009).

Medical-surgical nurses perform a

synergetic role when they receive support during a call for

RRTs, where the bedside nurse brought the patient information

to the situation. The RN in a RRT team provides the knowledge

and the skills for the consultation to medical surgical nurse,

and achieves role synergy characterised by RN-RN consultation

where what is achieved from interaction is greater than that

achieved from the individual efforts. The role of synergy

between RNs is to prevent adverse events from occurring during

the rescuing process. A synergic role is an effective and

an educational tool for both nurses and patient that supports

junior and new graduate nurses, and to have the full picture

about a patient who needs support and intervention. (Leach,

Mayo, O'Rourke, 2010).

According to Wehbe-Janek et al.,(2012)

simulation experiences for bedside nurses have been used to

increase their awareness of cases when a patient needs help.

A high fidelity simulator with realistic settings was used

to identify valuable components for the nurse. The simulation

program showed the relationship of the RRT associated with

the patient outcomes. An increased familiarity with the equipment

successfully increased their effective communication skills

and gave them a sense of familiarity with the role along with

its responsibility. Debriefing and reflective learning was

used, and suggested a key future for such simulations for

effective learning.

In medical-surgical nurses' experiences,

the decision to call an RRT when they became worried for their

patient was related to self-confidence. They would increase

their awareness of the patient's condition in order to decide

whether intervention from the RRT was needed (Jones et al.,

2006).

Feelings experienced when calling

an RRT differed from one nurse to another. Bedside nurses

sometimes experienced a positive interaction with the RRT

during the call, but while some of the nurses had positive

views, others did not. A few nurses indicated that they felt

afraid when they received criticism from an RRT after calling

them. However, some nurses indicated that RRT calls were required

because the medical management by doctors had been inadequate;

many ascribed this to junior doctors and a lack of knowledge

and experience. Some bedside nurses indicated that they would

call the RRT if they were unable to call the covering doctor;

however, a minority of medical-surgical nurses preferred to

call the doctor if there was a critically ill patient before

calling an RRT. (Williams, Newman, Jones, 2011).

According to Jones et al (2006) the

majority of ward nurses indicated that calling RRTs prevents

cardiac arrest, and 97 per cent said that the RRT intervention

was intended to help and manage an unwell patient. On the

other hand, a few nurses restricted their RRT calls because

they were afraid of criticism about their patient care.

Nurses' views concerning the benefits

of calling RRTs

According to Wynn et al. (2009), there were three main reasons

to call RRTs from the bedside nurses' point of view. Around

78 per cent of the nurses surveyed (n=75) indicated that the

primary reason they call a RRT is when there is a sudden change

in the patient's vital signs. The second reason, indicated

by 56 per cent of respondents, was when there was a steady

decline in the patient's condition. The third reason, 35 per

cent, was that no adequate response had come from the physician's

side.

Some studies have shown that in most

nurses' view, in their experiences, RRT helps critically ill

patients when they have any early signs of deterioration (Astroth

et al., 2013; Leach et al , 2013; Benin et al., 2012; Bagshaw

et al., 2010).

An RRT promotes the assessment and treatment by providing

a high level of knowledge and experience, as well as helping

the nurse to prevent calling code blue to their medical-surgical

ward. An RRT also transfers an ICU level of care to the patient

in order to secure their safety. The participating nurses,

from their own experiences, believed that RRTs could prevent

critically ill patients from having a cardiac or respiratory

arrest, and that they could prevent minor issues from becoming

major and potentially life-threatening problems (Astroth et

al., 2013).

Nurses thought that RRTs could help

patients who were deteriorating fast, and cited this as the

greatest advantage of RRTs. The participants described the

RRT as a pair of eyes to assess the situation (Williams et

al., 2011).

Bedside nurses receive immediate

assistance and help for any patient in a life-threatening

situation, with early intervention for critically ill patients

to prevent cardiac or respiratory arrest. Furthermore, RRTs

provide backup support for ward nurses when they are concerned

or dissatisfied with their current medical management, or

when the ward doctor is unavailable. This backup system gives

them peace of mind in a clinical setting, and a sense of security

in knowing that there is always a backup, providing the ward

nurse with access to a medical expert who knows how to manage

emergency situations (Salamonson et al, 2006).

The majority of medical-surgical

nurse participants reported that they call the RRT if there

is a complex medical-surgical issue. They also believed that

calling the RRT would help to prevent a critically ill patient

from having cardiac and respiratory arrest. A few nurses believed

that they call the RRT because nurses have inadequate management

(Bagshaw et al., 2010).

Knowledge and Skills of Bedside

Nurses

A medical-surgical nurse identified that the RRT is a supportive

team that provides guidance, education and continued follow-up

for the patient's condition. None of the nurses noticed any

discouragement from this team during calls. Furthermore, the

unit culture of teamwork and the willingness to care for each

other's patients during an RRT event gave them confidence,

knowing that they would receive the needed assistance (Astroth

et al., 2012).

The help from RRT and the improved

skills through working as a team was immediately available

through a single phone call for nurses, who were able to obtain

additional help without having to request permission. The

RRTs were the facilities' method of redistributing the workload

for nurses (Astroth et al., 2012; Benin et al., 2012).

The support provided in calls to

RRTs from medical-surgical nurses enhanced their skills and

increased their knowledge and awareness in the processes of

nursing when they had critically ill patients. This especially

benefitted new graduate nurses, allowing them to learn from

the role of the RRTs. Some new nurses believed that calling

the RRT represented a positive and collaborative experience

that reinforces the use of teamwork. Patients also benefit

from this team when intervention occurs quickly, and as some

nurses noted, it helps them to practice their skills every

day (Williams et al., 2010).

According to Wehbe-Janek et al. (2012),

the simulation-training programme enhanced nurses' knowledge

and skills relating to medical emergency situations. An RRT

allowed them to identify their weaknesses and to learn from

their mistakes or lack of knowledge, particularly in regards

to the uncomfortable issues that they have to become familiar

with during some proper procedures, such as using an algorithm

and a crash cart. Other nurses felt that sharing ideas and

tasks expedited the assessment process and ultimately improved

the patient's condition at a faster rate.

Bedside nurses were satisfied with

the collaboration with the RN RRTs, and noted that the outcome

of the RRTs was often an improvement in skills and experiences.

However, bedside nurses also wanted to be engaged with the

team in order to provide better care for their patients, especially

when the RRT call was over and they had to care for the patient

remaining in the unit. Nurses noted that the RRTs brought

about a greater sense of appreciation for the nurses after

an RRT call, where some family members of a patient made positive

comments about their support and how they helped to save lives.

The opinion of the nurses in this study proved that they valued

RRTs, and demonstrated the positive effects that the RRTs

bring to their everyday practice. The implied positive effect

is support and empowerment for nurses (Williams et al., 2010).

Some participants amongst medical-surgical

nurses found that understanding the criteria for calling the

RRT and knowledge were important to meet the patients' needs

and to identify unstable patients. Education is important

in providing skills that will help patients (Brown, Anderson,

Hill, 2012).

Nurses' familiarity with using

the criteria for calling the RRT

When a bedside nurse calls the RRT for a critically ill patient,

he or she uses the criteria for calling the RRT based on his

or her knowledge. Critical knowledge experiences are important

in managing the crisis, and this is based on nurses' experiences

(Galhotra et al., 2006).

According to Leach & Mayo (2013)

medical-surgical nurses described that familiarity with the

team leads to trusting behaviour between them when there is

an urgent case.

The majority of participants expressed

familiarity with the RRT criteria. Around 90 per cent of nurses

thought that the RRT programme improved patient care, and

around 84 per cent felt that the service improved the nursing

work environment. Nurses who had called an RRT on more than

one occasion were more likely to value their ability to do

this (Pusateri et al., 2011).

The other nurses expressed that in their experience, the RRTs

improved their practice, since they are supported by the RRTs

when they know the criteria. Furthermore, they stated that

they receive encouragement from the nursing leader and other

co-workers. Participants in this study noted that they felt

confident when they called an RRT. Medical-surgical nurses

indicated that they received their education about RRTs during

their annual competency review. A few noted that they did

not receive any education on the RRT, other than when the

RRT was developed. Participants believed that newly graduated

nurses needed to be educated about RRTs in order to gain more

awareness about when they should call this team and for what

reasons (Astroth et al., 2012).

Communication Skills for Calling

an RRT

Nurses enhance their communication skills as another valuable

component of simulation training. Several participants described

the RRT members' communication skills as being professional

and caring. Both bedside nurses and the RRT members used the

communication tool SBAR to collect information during the

event, since this tool provides information both quickly and

accurately. The participants noted that many of the RRT nurses

provided emotional support. Others commented that they provide

encouragement to bedside nurses, and use humour to defuse

a tense situation. (Astroth et al., 2012).

In the case of an inadequately experienced

bedside nurse, he or she is required to call the RRT in an

emergency case, whereas other nurses would call the physician

first when they have a sick patient. It was noted that 55.9

per cent from the total of 351 participants that they would

call the RRT even if they were worried about any changes in

the vital signs, in order to increase their knowledge through

interaction with the RRT (Jones et al., 2006).

Common Challenges for

Nurses When Calling RRTs

Knowledge and Experiences

A lack of knowledge and experience can lead to a lack of confidence

and feelings of discomfort. Being faced with a need to exercise

judgment and decide whether or not to call the RRT is a challenge

for some bedside nurses when a medical-surgical nurse has

noticed that a patient meets the criteria for calling an RRT.

Furthermore, a lack of knowledge will lead to low quality

of patient care (Schmid, Hoffman, Wolf, Happ, & Devita,

2013).

A few medical-surgical nurses were

reluctant to call an RRT for fear of criticism from the RRT

team when they responded to the call. (Jones et al 2006)

Conflict Between the Bedside Nurse

and the Rapid Response Team

Working as a team is a major part of delivering good care

to a patient and saving patients' lives. However, in the case

of a conflict between the primary team and the nurses, or

between the primary team and the RRTs, the bedside nurses

attending felt that their plans for the patients were disrupted,

resulting in disjointed care for the patient. This is a challenge

concerning which team the bedside nurse will follow. As another

study shows, these challenges are listed under the following

two categories: direct challenge, when it is difficult to

know when to call the RRT or not, and indirect challenge,

when the RRT has been called and the question is who should

take care of the patient during the RRT's call out (Shapiro

et al., 2010).

Level of Education

Professionals who are to join RRTs need more education, training

and understanding about the philosophy behind RRTs. Other

challenges include the attitudes of RRT staff when they respond

to calls from the bedside nurses. One nurse participant noticed

that their individual's voice and communication style had

a frustrated tone, which was not encouraging during the call

out (Salamonson et al., 2006).

Traditional hierarchies and their

relation to the physicians and supervisors impede some of

the components of RN decision-making during rescue (Leach

et al., 2010).

Other nurse participants identified

that they were worried about calling RRTs because they felt

afraid of criticism from them. Other nurses feared calling

RRTs without the knowledge of the responsible nurses and physicians;

nurses observed the reaction of the team, and this made them

reluctant to call the RRT the next time. Other nurses described

situations where they wanted to call RRTs, but were reluctant

that they would be perceived as having neglected to give care

to patients (Astroth et al., 2012).

Three different studies found that

communication was a challenge when calling RRT members who

did not exhibit a communication style that the nurses perceived

as being supportive. According to the participants, their

body language and method of questioning were perceived as

negative and condescending. Moreover, their tone of voice

was not encouraging to the bedside nurse. Furthermore, the

lack of knowledge regarding the institution's policy on calling

RRTs added a confusing barrier, making the nurse reluctant

to make the call (Astroth et al., 2012; Jones et al., 2006;

Baldwin et al., 2006).

According to Bagshaw et al. (2010)

and Wehbe-Janek et al. (2012), there are other challenges

facing nurses who want to call RRTs: they become frustrated

with the delay in care when physicians are not present to

assess their patients, and they have to resist calling the

RRTs. Unavailability of assistance from co-workers created

a demand for nurses to work around the clock, losing precious

time when they should be providing care for their patient.

Some nurses identified enhanced communication as another value

of simulation training, since they were unaware of clear communication

procedures. The lack of confidence and comfort flowed in the

simulation where feelings were concerned.

Many nurses indicated that they would

not call an RRT without calling a physician first, and some

nurses feared that some doctors would shout at them when they

called the RRT. 84 per cent disagreed or strongly disagreed

that using an RRT system would increase their workload when

caring for their patients. The poor attitude from some RRTs

seems to require more education in order to deliver good communication

between the team and the staff member who is taking care of

the patient (Salamonson et al., 2006).

Discussion

Method

The literature review method was used in this study to compile

and summarise findings; each article was read and critiqued

separately and critically appraised starting with the title,

year of publication, and abstract. Next, the whole article

was analysed, including the background, aim, sampling method,

data collection, data analysis, results, discussion and ethical

approval. References were also checked for validity, credibility

and reliability. The classification of each article was assigned

following the guidelines of the quality grade (see Appendix

II). This helped the author to choose the articles that best

supported the aim. Most articles were grade I and the rest

were grade II. Graded I articles included clear abstracts

and clear processes of research, while grade II articles were

less clear in some respects.

Ethical principles were used in the

search process, including honesty, copyright for publication

and avoiding any plagiarism or misconduct such as falsification

and fabrication.

Some difficulties were faced when

searching for articles in the PubMed database. Some articles

provided more information but their year of publication was

more than 10 years ago; other articles would not open. MeSh

terms were used to find more articles relating to the topic

and to address the aim of the study. The 15 articles represented

research in different countries, but most focussed on US hospitals,

while a few were conducted in Australia.

Other challenges during the time

of this study included a lack of search results from the MeSh

database; consequently, the free search in PubMed was used.

All articles were published between the years 2005 and 2013.

Some of the articles were randomised controlled trials (RCTs),

whereas others were qualitative and prospective studies. (Poilt

& Beck, 2012).

Results

This review looked at nurses' experiences and the challenges

that medical-surgical nurses face when they call an RRT for

an urgent patient case. During the analysis of all 15 articles,

the results were categorised under the headings of 'experiences'

and 'challenges'. All of these articles addressed the research

questions and explored bedside nurses' experiences when calling

RRTs. They found that the RRT is a helpful system for patients,

and that bedside nurses felt supported by RRTs. However, there

were some challenges that needed to be overcome in order to

have a successful team delivering a good quality of care to

the patient from the points of view of both medical-surgical

nurses and the RRTs.

The themes of level of experience

and qualifications largely reflected what the nurses experienced

when calling RRTs. The findings emphasise that RRTs are an

effective tool for patient care that saves patients' lives

by preventing medical error and other adverse events (Winters

et al., 2006; Brindley et al., 2007). However, there are many

factors that can affect the performance of the system, including

human error, poor communication, and deficiency in leadership,

all of which could apply to the nursing team or the RRT (Raynard,

Reynolds, & Stevenson, 2009).

The nurses' experiences with decision-making

in trying to give quick and helpful intervention for patients

focussed on the RRT for urgent and critical cases. Nurses

are faced with the need to make a decision that requires years

of experience combined with a high level of education. Nurses

at the baccalaureate level with more than five years of experience

had self-initiated calls to an RRT for urgent cases. Thus,

education and experience are important when it comes to independent

calling. Nurses who have more experience tend to have expertise

in recognising and interpreting a situation, and are therefore

better able to manage it. All hospitals have the responsibility

to educate all healthcare professionals in order to improve

the outcome for each patient. It is important to educate nurses

about the RRT system, especially when it comes to new graduates

(Wynn et al., 2009). Feelings of worry were major reasons

for a bedside nurse to call the RRT, along with degree of

empowerment and independent action by the nursing staff. Nurses

need to know when and how to call an RRT in serious situations

(White, Pichert, Bledsoe, Irwin, & Entman, 2005; Santiano

et al., 2009).

Nurses' experiences when activating

the RRT protocol differed according to their use of the RRT

criteria, different levels of education and diverse experiences.

Some hospitals have their own protocol for calling the RRT,

and this may be different from one hospital to another (Moldenhaure

et al., 2009; Santiano et al., 2009). Decisions to call the

RRT for critically ill patients by the bedside nurse are based

on knowledge and the skills that come with years of experience

and satisfaction with RRTs. This helps them to identify the

best decision and when to call the RRT, but their qualifications

also play a role in this (Metcalf et al., 2008).

Medical-surgical nurses stated that

RRTs provide important assistance when the early signs of

deterioration are identified in order to prevent an adverse

event so as to save patients' lives. RRTs also create a teamwork

situation that generates communication among professionals,

and this communication becomes more effective when a bedside

nurse uses SBAR when reporting on the arrival of other team

members (Beebe, Brinkley, & Kelley, 2012).

Poor communication between a bedside nurse and the RRT leads

to an improper response. This indicates that poor communication

is a barrier to engaging in effective action when a patient

is critically ill, and that it is necessary to enhance nurse-physician

communication to ensure that when a nurse calls an RRT, the

response is appropriate. (White et al., 2005).

Medical-surgical nurses did not believe

that RRTs are overused in hospitals, and other participants

believed that interaction with the RRT did not increase their

workload or decrease their skills when they gave care to a

patient, but rather provided an opportunity for education

(Jolly, Bendyk, Holaday, Lombardozzi, & Harmon, 2007).

It was also considered that RRTs increase the knowledge of

the bedside nurses indirectly through the following of simulation

training, enhancing skills and awareness preparedness for

emergency team events. This was amplified by the strong response

that nurses have a better understanding of the roles of the

RRT following training (Potter & Perry, 2008). RNs in

RRTs have a synergetic role when it comes to both patients

and bedside nurses. The American Association for Critical

Care Nursing developed the synergy model, which defines some

common characteristics for patients and nurses. (Hardin,Kaplow,2005)

The patient characteristics are vulnerability,

stability, complexity and predictability. Keeping these in

mind, the nurse will be able to provide the best care according

to patients' needs. In terms of vulnerability, nurses look

for actual and potential stressors, whether physiological

or psychological, which might affect patient outcomes. Highly

vulnerable patients are susceptible to further deterioration

and poor outcomes. Stability involves maintaining a steady

equilibrium and assessing this characteristic means evaluating

a patient's ability to respond to the treatment. Meanwhile,

complexity involves the interaction of two or more systems,

and is found when patients are treated for complicated diagnoses.

Here, the nurse will assess patients for their response to

treatment and other unknown factors. Predictability is important

when it comes to nurses' identification of a predictable path

based on the disease progress and potential complications.

Here, the nurse must synthesise patient data with disease

management guidelines to ensure favourable outcomes.

The nurse characteristics are clinical

judgment, advocacy and moral agency, caring practice and collaboration.

Clinical judgment is clinical reasoning which includes decision

making, critical thinking and the global grasp of a situation

according to experiential knowledge and evidence-based guidelines.

When registered nurses are not part of an RRT, this team educates

bedside nurses' in relation to their clinical judgment through

physical and data assessment techniques that are anticipated

to be helpful for the patient. Such tools are useful for critical

care nurses when they are unfamiliar with these techniques.

In terms of advocacy and moral agency, a nurse will demonstrate

moral agency by working on the behalf and representing the

concerns of the patient. As an advocate, the RRT nurse will

be able to direct patient-centred care and ensure that patients'

wishes, dignity and rights are preserved. Moreover, in this

way, the team will provide support to patients and family

by offering clear information about the patient's condition.

The RRT also helps bedside nurses to promote decision-making.

The team acts as a conduit to exchange information amongst

the nurse, family and patient. Collaboration involves working

with others such as physicians, families and healthcare providers

in a way that promotes and encourages effective care. Each

team must respect the other teams and the role they play in

ensuring that their patient has a positive outcome (Hardin

& Kaplow, 2005).

The implementation of the RRT in

a hospital to save patients' lives distributes the work across

a team of bedside nurses, physicians and RRT members. The

RRT increases the sense of security among medical-surgical

nurses when managing an unwell patient and this may translate

into more confidence and empowerment for the nurse (Jolly

et al., 2007).

Some bedside nurses noted that they

learn new skills from interactions with RRTs, while some observed

that they want to have a special programme concerning the

RRT in order to understand when to make a call (Brown et al.,

2012). Team communication and information sharing is a critical

part of team behaviour; the Joint Commission report indicated

that communication failure is a root cause of essential events

(The Joint Commission, 2007). Communication is thus important

in delivering good care. The following three main factors

are associated with communication failure: (i) Physicians

and nurses are trained to communicate differently; (ii) the

hierarchies within the health care systems frequently inhibit

people from speaking up; and (iii) the communication and the

providers in health care (Leonard, Graham, & Bonacum,

2004).

Medical-surgical nurses and physicians

need to work as a team and accept each other's ideas. Teamwork

results in the delivery of good care to patients, as the patient

is the main concern for nurses, physicians and the RRT. Some

nurses stated that when faced with a patient who meets the

criteria for an RRT, they should call a responsible physician

before calling the RRT itself. This result suggests that the

nurse would prefer to use diplomacy instead of calling the

RRT. However, if there were no physician available, the participants

indicated that they would call the RRT (DeVita et al., 2006).

Some physicians believe that the

RRTs interfere with their plans, and this finding suggests

that more education for both nurses and physicians is needed

regarding the role of RRTs (Jolly et al., 2007). On the other

hand, delays in quick intervention relating to the lack of

a clear understanding about roles of RRTs have been a problem

when it comes to taking responsibility for whether or not

an RRT should be called. It has been suggested that simulation

training clarifies this role and increases awareness and preparedness

(Villamaria et al., 2008).

Education and teaching for bedside

nurses will improve their skills when it comes to calling

the RRT for their patients without the feeling of criticism.

More extensive education is needed in order to remove the

feeling of hesitation in calling the RRT (Pustateri, Prior,

& Kiely, 2011).

Conclusion

Medical-surgical nurses call RRTs

to help save patients' lives, and their decisions depend on

their prior experience. Medical-surgical nurses and RRTs need

to collaborate during the delivery of care to patients. Both

need to have knowledge and good communication skills in order

to identify the deteriorating clinical signs that require

intervention and to deliver fast intervention to a critically

ill patient.

The experiences of bedside nurses

who have become familiar with the signs of a deteriorating

patient and who know the criteria for calling RRT play a major

role. Years of experience and levels of qualification are

crucial in a nurse's decision to call the RRTs or to refrain

from doing so. Furthermore, the communication and attitude

of the bedside nurse and the RRT member play a large role

in delivering clear information. Finally, the patient needs

help and protection from any adverse event which could occur

while receiving care in hospital. An RRT is a helpful tool

for hospitals to apply, and can be used to educate staff.

When a patient stays in the hospital because of a medical

error, this team is needed.

Clinical Implications

The author found that, when employing RRTs in a hospital setting,

it is important to focus on educating new staff alongside

all nurses and physicians who have prior experiences with

RRTs. They should be given strategies on what their role will

be when they are faced with the need for emergency care. Education

about RRTs is important in order to avoid miscommunication

and misunderstanding between the staff that take care of patients'

wellbeing.

Recommendations for Further Studies

The author found that more studies regarding medical-surgical

nurses' perspectives on education are required in order to

address the challenges facing new staff when they call RRTs

to save their patient's life. Additional studies should also

focus on the area of improving communication among the members

of the medical-surgical team and on communication attitudes.

Click here for

Appendix 1

Click here for Appendix

2

References

Alqahtani, S., Aldorzi, H., Alknawy, B., Arabi, Y., Fong,

L., Hussain, H., et al. (2013). Impact of an intensivist-led

multidisciplinary extended rapid

response team on hospital-wide cardiopulmonary arrests and

mortality. Society of Critical Care Medicine, DOI:10.1097.

Abella, B. S., Alvarado, J. P., Myklebust, H., Edelson,

D. P., Barry, A., O'Hearn, N., Vanden Hoek, T. L., & Becker,

L. B. (2005). Quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation during

in-hospital cardiac arrest. Journal of the American Medical

Association, 293(3), 305-310.

American Nurse Association (2011). Code of ethics for nurses

with interpretive statements. Retrieved October 21, 2013 from

http://www.nursingworld.org/Mobile/Code-of-Ethics/provision-4.html

Astroth, K., Woith, W., Stapleton, S., Degitz, R., & Jenkins,

S. (2012). Qualitative exploration of nurses' decision to

activate rapid response teams. Journal of Clinical Nursing,

22, 2876-2882.

Aveyard, H. (2010). Doing a literature review in health and

social care: A practical guide (2nd ed.). Maidenhead: Open

University Press.

Azzopardi, P., Kinney, S., Moulden, A., & Tibballs, J.

(2011). Attitudes and barriers to a medical emergency team

system at a tertiary paediatric hospital. Resuscitation, 82(2),167-176.

Bagshaw, S. M., Mondor, E. E., Scouten, C., Montgomery, C.,

Slater-MacLean, L., Jones, D. A., et al. (2010). A survey

of nurses' beliefs about the medical emergency team system

in a Canadian tertiary hospital. American Journal of Critical

Care, 19(1), 74-83.

Bellomo, R., Goldsmith, D., Uchino, S., Buckmaster, J., Hart,

G., Opdam, H., et al. (2004). Prospective controlled trial

of effect of medical emergency team on postoperative morbidity

and mortality rates. Critical Care Medicine, 32(4), 916-921.

Benin, A.L., Brogstrom, C. P., Jenq, G.Y., Roumanis, S. A.,

& Horwitz, L. (2012).

Defining impact of a rapid response team: Qualitative study

with nurses, physicians and hospital administrators. British

Medical Journal, 21, 391-398.

Berg, A., Dencker, K., & Skarsater, I. (1999). Evidensbaserad

omvardnad:Vid behandling av prisoner med depressinssiukdomar

(Evidensbaserad Omvarn, 1999:3). Stockholm, Sweden: SBU, SFF.

Brindley P,G., et al., (2007). Best clinical evidence feature.

Medical Emergency Teams: Is there M.E.R.I.T? Canadian Journal

of Anaesthesia, 54(5), 389-91.

Brown, S., Anderson, M., & Hill, P. (2012). Rapid response

team in a rural hospital. Clinical Nurse Specialities, 26,

95-102.

Beebe, P., Brinkley, K., & Kelley, C. (2012). Observed

and self-perceived teamwork in a rapid response team. Journal

for Nurses in Staff Development, 4, 191-197.

Buist, M. D., Moore, G. E., Bernard, S. A., Waxman, B. P.,

Anderson, J. N., & Nguyen, T.V. (2002). Effects of a medical

emergency team on reduction of incidence of and mortality

from unexpected cardiac arrests in hospital: Preliminary study.

British Medical Journal, 324(7334), 387-390.

Buntner, S,C. (2011). Rapid response team effectiveness. Dimensions

of Critical Care nursing , 30(4), 201-205.

Burkhardt, M., & Nathaniel, A., (2008). Ethics issues

in contemporary nursing. (3rd ed.). York: Delmar.

Chamberlain, B., & Donley, K., (2009). Patient outcomes

using a rapid response team. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 23(1),

11-12.

Cretikos, M., Parr, M., Hillman, K., Bishop, G., Brown, D.,

Daffurn, K., et al. (2006). Guidelines for the uniform reporting

of data for medical emergency teams. Resuscitation, 68(1),

11-25

Coughlan, M., Cronin, P., & Ryan, F. (2013). Doing a literature

review in nursing, health and social care. London, UK: SAGE.

Curtis, R, J. (2008). Caring for patients with critical illness

and their families: The value of the integrated clinical team.

Respiratory Care, 53(4), 480-487.

Chan, P. S., Jain, R., Nallmothu, B. K., Berg, R. A., Sasson,

C., (2010). Rapid Response Teams: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Arcb Intern Med, 170(1), 18-26.

Dacey, J., Mirza, R., Wilcox, V., Doherty, M., Mello, J.,

Boyer, A., Gates, J., Brothers, T., & Baute, R. (2007).

The effect of a rapid response team on major clinical outcome

measures in a community hospital. Critical Care Medicine,

35(9), 2076-2082.

DeVita, M., Bellomo, R., Hillman, K., Kellum, J., Rotondi,

A., Teres, D., et al . (2006). Finding of the first consensus

conference on medical emergency team. Critical Care Medicine,

34(9), 2463-78.

DeVita, M., Hillman, K., & Bellemo, R. (2011). Rapid response

system concept and implementation. New York, NY: Springer.

Donaldson, N., Shapiro, S., & Scott, M. (2009). Leading

successful rapid response team: A multisite implementation

evaluation. Journal of Nursing Administration, 39(4), 176-181.

Dwyer, T., Mosel, W. L. (2002). Nurses' behaviour regarding

CPR and the theories of reasoned action and planned behaviour.

Resuscitation, 52(1), 85-90.

Galhotra, S., Scholle, C. C., Dew, M. A., Mininni, N. C.,

Clermont, G., & DeVita, M. A. (2006). Medical emergency

teams: A strategy for improving patient care and nursing work

environments. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 55(2), 180-7.

Geoffrey, L., Parast, L., Rapoport, L., Wagner, T. (2010).

Introduction of a rapid response system at a United States

veterans affairs hospital reduced cardiac arrest. Anaesthesia

and Analgesia, 111(3), 679-686.

Green, A., & Allison, W. (2006). Staff experiences of

an early warning indicator for unstable patients in Australia.

Nursing Critical Care, 11(3), 118-27.

Hijazi M, M., Sinno, M., & Alansar, M., (2012). The Rapid

Response Team reduces the number of cardiopulmonary arrests

and hospital mortality. Emergency Medicine, doi.org/10.4172/2165-7548.1000128.

Hardin,S.P., & Kaplow,R. (2005). Synergy for clinical

excellence: The AACN synergy model for patient care. Sudbury,

MA:Jones And Bartlett.

Hatler, C., Mast, D., Bedker, D., Johnson, R., Corderell,

J., Torres, J., et al. (2009). Implementing a rapid response

team to decrease emergencies outside the ICU: One hospital's

experience. Medical Surgical Nursing, 18(2), 84-90, 126.

Hillman, K., Chen, J., Cretikos, M., Bellomo, R., Brown, D.,

Doig, G., et al. (2005). Introduction of the medical emergency

team (MET) system: A cluster-randomized controlled trial.

Lancet, 365, 2091-2097.

Institute for Clinical System Improvement. (2013). Healthcare

protocol rapid response team. Retrieved October 16, 2013 from

https://www.icsi.org/_asset/8snj28/RRT.pdf.

Institute of Healthcare Improvement. (2001). Protecting 5

million lives from harm. Retrieved September 16, 2013 from

http://www.ihi.org/offerings/Initiatives/PastStrategicInitiatives/5MillionLivesCampaign

/Pages/default.aspx.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement. (2010). Heading off

medical crises at Baptist Memorial Hospital. Retrieved October

22, 2013 from http://www.ihi.org/knowledge/Pages/ImprovementStories/RapidResponseTeamsHeadingOffMedical

CrisesatBaptist MemorialHospitalinMemphis.aspx

Institute of Healthcare Improvement. (2013a). SBAR technique

for communication: A situational briefing model. Retrieved

September 16, 2013 from http://www.ihi.org/knowledge/Pages/Tools/SBARTechniqueforCommunicaton

AituationalBriefingModel.aspx.

Institute of Healthcare Improvement. (2013b). Vision, mission,

and values. Retrieved September 20, 2013 from http://www.ihi.org/about/Pages/IHIVisionandValues.aspx

Institute of Health Care Improvement.

(2011). Establish criteria for activating the rapid response

team. Retrieved September 20, 2013 from http://www.ihi.org/knowledge/Pages/Changes/EstablishCriteriaforActivating

theRapidResponseTeam.aspx.

International Council of Nurses. (2012). Code of ethics. Retrieved

September 16, 2013 from http://www.icn.ch/images/stories/documents/about/icncode_english.pdf.

Jenkins, S. D., & Lindsey, P. L. (2010). Clinical nurse

specialists as leaders in rapid response. Clinical Nurse Specialist,

24(1), 24-30.

Jolly, J., Bendy, K. H., Holaday, B., Lombardozzi, K.A., &

Harmon, C. (2007). Rapid response team: Do they make a difference?

Dimensions of Critical Care nursing, 26,(6) 253-60

Jones, D., Baldwin, I., McIntyre, T., Story, D., Mercer, I.,

Miglic, A., et al. (2006). Nurses' attitudes to a medical

emergency team service in a teaching hospital. Quality and

Safety in Health Care. 15(6), 427-32.

Keller, S., Edstrom, A., Parker, W., Gabriele, C., & Kriewald,

M. (2012). Scope and standard of medical surgical nursing

(5th ed.): Academy of Medical Surgical Nurses.

Kemper, K., Bulla, S., Krueger, D., Ott, M. J., McCool, J.

A., & Gardiner, P. (2011). Nurses' experiences, expectations,

and preferences for mind-body practices to reduce stress.

BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 11, 1-9.

Konrad, D., Jäderling, G., Bell, M., Granath,F., Ekbom,

A., Martling, C. (2009). Reducing in-hospital cardiac arrests

and hospital mortality by introducing a medical emergency

team. Intensive Care Medicine. 36(1), 100-6.

Leach, L., Mayo, A., & O'Rourke (2010). How RNs rescue

patients: A qualitative study of RNs' perceived involvement

in rapid response teams. British Medical Journal, 19, 13.

Leonard,M., Graham, S., & Bonacum, D. (2004). The human

factor: The critical importance of effective teamwork and

communication in providing safe care. Quality Safe in Health

Care, 13(1), 85-90.

Leach,L.S.,& Mayo,A.M.(2013). Rapid response team: qualitative

analysis of their effectiveness. American Journal of Critical

Care,22:198-210.

Metcalf, R., Scott, S., Ridgway, M., Gibson, D., et al. (2008).

Rapid response team approach to staff satisfaction. Orthopaedic

nursing, 27(5), 266-71.

Clinical triggers: An alternative to a rapid response team.

Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 35(3),

164-74.

Wynn, J., Engelke, M., Swanson, M. (2009). The front line

of patient safety: Staff nurses and rapid response team calls.

Quality Management in Health Care, 18(1), 40-47.

Moldenhaure, K., Sabel, A., Chu, E. S., & Mehller, P.

S. (2009). Clinical triggers: An alternative to a rapid response

team. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety,

35(3), 164-74.

National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2013). Nurse

practice act, rules & regulations. Retrieved October 20,

2013 from https://www.ncsbn.org/1455.htm.

National Patient Safety Agency (2007). Safe care for the acutely

ill patient: learning from serious incidents. London: NPSA.

National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Out Come And Death.

(2005). An acute problem? A report of the national confidential

enquiry into patient out come and death. London: NCEPOD.

Peberdy, M. A., Kaye, W., Ornato, J. P., Larkin, G. L., Nadkarni,

V., Mancini, M. E., et al. (2003). Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

of adults in the hospital: A report of 14,720 cardiac arrests.

The National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation, 58(3),

297-308.

Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2012). Nursing research:

Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (8th

ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Potter, P. A., & Perry, A. G. (2008). Fundamentals of

nursing. (7th ed.) Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Pusateri, M. E., Prior, M. M., & Kiely, S. C. (2011) The

role of the non-ICU staff nurse on a medical emergency team:

Perceptions and understanding. American Journal of Nursing,

111(5), 22-29.

Ray, E. M., Smith, R., Massie, S., Erickson, J., Hanson, C.,

Harris, B., & Willis, T. S., (2009). Family alert: Implementing

direct family activation of a pediatric rapid response team.

Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 35(11),

575-580.

Rogers, A., Hwang, Ting Hwang, S., Aiken, L., & Dinges,

D. F. (2004). The working hours of hospital staff nurses and

patient safety. Health Affairs, 23(4), 202-212.

Santiano, N., Young, L., Hillman, K., Parr, M., Javasinghe,

S., & Baramy, L. S. (2009). Analysis of medical emergency

team calls comparing subjective to objective call criteria.

Resuscitation, 80(1), 44-49.

Salamonson, Y., Heere, B., Everett, B., & Davidson, P.

(2006). Voices from the floor: Nurses' perception of the medical

emergency team. Intensive And Critical Care Nursing, 22, 138-143.

Shapiro, S., Donaldson, N., & Scott, M., (2010). Rapid

response teams seen through the eyes of the nurse. American

Journal of Nursing, 110(6),28-34.

Sharek, P. J., Parast, L. M., Leong, K., Coombs, J., Earnest,

K., Sullivan, J., Frankel, L.P, & Roth, S. J. (2007).

Effect of rapid response team on hospital-wide mortality and

code rates outside the ICU in a children's hospital. Journal

of the American Medical Association, 298(19), 2267-2274.

Scott, S., & Elliott, S. (2009). Implementation of a rapid

response team: Success story. Critical Care Nurse, 29 (3),66-75.

Schmid, M., Hoffman, L.A., Wolf, G. A., Happ, M. B., &

DeVita, M. A. (2013). The use of medical emergency teams in

medical and surgical patient: Impact of patient, nurse, and

organisation characteristics. Quality Safe in Health Care,

17, 377-381.

The Joint Commission. (2007). National Patient Safety Goal.

Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission: 2007.

Thomas, K., Force, M., Rasmussen, D., Dodd, D., & Whildin,

S. (2007). Rapid response team, challenges, solutions, benefits.

Critical Care Nurse, 27(1), 20-27.

Villamaria, F., Pliego, F., Wehbe-Janke, H., Coker, N., Rajab,

H., et al. (2008). Using simulation to orient code blue team