| |

February

2014

- Volume 8, Issue 1

Nurse-led chest

drain clinic: a case study of change from national health

system in UK

|

( (

|

Abdulsalam

Y Taha (1)

Akeel S Yousr (2)

Kamil J Zaidan (3)

(1) Prof. Abdulsalam Y

Taha, Department Of Thoracic And Cardiovascular Surgery,

School Of Medicine, University Of Sulaimania And Sulaimania

Teaching Hospital, Sulaimania, Region Of Kurdistan,

Iraq. E MAIL: salamyt_1963@hotmail.com PHONE: 009647701510420

(2) Dr. Akeel S Yousr, Department Of Thoracic And Cardiovascular

Surgery, Ibn-Alnafis Teaching Hospital For Thoracic

And Cardiovascular Surgery, Baghdad, Iraq.

(3) Dr. Kamil J. Zaidan, Kadimia Teaching Hospital,

Baghdad, Iraq.

Correspondence:

Prof. Abdulsalam Y Taha,

Head of Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery,

School of Medicine, University of Sulaimania, Sulaimania,

Region of Kurdistan, Iraq

PO Box: 414.

Phone: 009647701510420

Email: salamyt_1963@hotmail.com

|

|

|

Abstract

Background and Objective: There are many nurse-led

clinics now in the UK, such as Chest-Pain, Endoscopy

and Bronchiectasis Clinics. Herein, we present the project

of Nurse-led Chest Drain Clinic in Guy's and St Thomas,

s Hospital, London. The aim is to analyze this change

project.

Methods: A project of change was designed to

set up an outpatient clinic run by specialist clinical

nurses for patients discharged home with an ambulatory

chest drain system in situ. The project is observed

and analyzed via interviews with the responsible nurses.

Results: The clinic was established in 2005 and

run by two Nurse Case Managers. 60 patients were seen

in 2007 and the clinic remained well attended. Patients

were happy to spend less time in hospital as they could

stay safely with their families.

Conclusions: A safe at home management of long-term

chest drains was provided by this nurse-led clinic.

Key words: chest drain, nurses, outpatient clinic

|

Introduction

The National Health System in the United Kingdom (UK) has

witnessed dramatic changes in the role of nurses over the

last 2 decades. The professional standard of nurses has very

much improved. The public has realized this change and their

trust in services provided by nurses has also increased. There

are many clinics now in the UK run by specialized nurses such

as Chest-Pain Clinic, Endoscopy Clinic, Bronchiectasis Clinic

and others.[1,2] Thoracic surgery is no exception. Patients

with chest drains placed for different indications like drainage

of air and/or fluid in the pleural space are usually managed

in hospital till the drainage stops and the chest tube is

removed. This sometimes necessitates a long stay in hospital

for persistent air and/or fluid drainage. This is undoubtedly

associated with increased cost and burden on hospital resources.

More time should be spent by physicians looking after such

patients until they can be discharged home with no chest drain.

Herein, we present the project of Nurse-led Chest Drain Clinic

in Guy's and St Thomas's Hospital, London. The aim is to analyze

the process of successful change achieved by nurses in this

project.

Materials and Methods

A project of change was designed to set up an outpatient clinic

run by clinical nurse specialists for patients discharged

home with an ambulatory chest drain system in situ. The project

is observed and analyzed via interviews with the responsible

nurses. Place: the clinic was located at Guy's Hospital in

the Cardiothoracic Outpatient Department, 1st Floor, Thomas

Guy's House.

Clinic Times: Monday afternoon 14.00 to 16.00, 4 slots

of 30 minutes per patient.

It was run by 2 Nurse Case Managers; both had specialized

thoracic surgery skills and experience.

Patient Population: any patient with a chest drain

in situ who can be managed at home by a District Nurse, or

patients who had recently had a chest drain in hospital and

required follow up.

On discharge home, the patient was given an information sheet

and his/her District Nurse was informed by phone about the

care of chest drain at home. The first appointment would be

after 1 week. The nurse would assess level of fluid output

and/or history of air leak. A chest X-ray would be ordered

and reviewed by the clinic nurse specialist with the consultant

thoracic surgeon or registrar. A clinical decision was to

be made as to remove or keep the drain. Chest drain would

be removed by the nurse when necessary. The consultant's message

was clear: whenever in doubt, do not remove the chest drain.

A letter would be written to the GP, thoracic surgeon or the

oncologist. A weekly follow up was necessary as long as the

drain remained in situ.[3] Most patients with air leak could

have their chest drain removed in 2 weeks. Examples of the

devices used in patient's care are shown in Figures 1-3. The

community nurses used to be afraid of caring for a patient

with a chest drain. This fear was alleviated by annual workshops

held in the department to educate them about chest drain care

and other health topics.

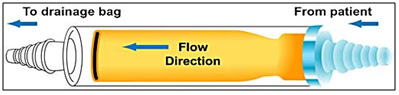

Figure 1: Heimlich chest drain valve

Source: www.medicine-on-line.com

image 011

Figure 2: Heimlich valve attached to chest tube

Source: www.vygonvet.co.uk

Figure 3: a plastic bag attached to chest drain.

Source: The Guy's and St Thomas, NHS Foundation Trust December-2007

Newsletter

Results

The change took about 6 months. The clinic was established

with co-operation of the consultant surgeons and other stakeholders.

The actual work in the clinic began in 2005. An audit of all

patients visiting the clinic was kept by the Nurse Case Manager

on Excel. Numbers and outcomes were recorded. During the year

2007, 60 patients were seen i.e., 5 patients per week. "The

Chest Drain Clinic remains well-attended, we see an increase

in the number of patients managing their long-term drains

at home and we are happy for patients to spend less time in

hospital when they prefer to be at home closer to their families"[4]

said the nurse case managers. Patients and their relatives

felt happier, being earlier discharged and staying at home.

Discussion

The Thoracic surgical department in Guy's Hospital at the

time of the study had 4 consultant thoracic surgeons, 2 senior

nurses and 28 beds.[3] The number of beds was considered relatively

small in relation to the size of the served population (estimated

to be around 15 million persons).[3,4] It is well known that

patients with persistent air leak and/or fluid drainage may

occupy beds for a long time thus putting a burden on hospital

resources. The few surgeons in the department used to spend

a considerable time in the follow up of such patients.

The idea of shifting the care of patients with chest drains

after leaving the hospital, from doctors to nurses, was thus

born for many reasons. The Guy's and St Thomas, NHS Foundation

Trust encouraged projects which aimed at a better use of beds,

providing enough beds for cancer patients which comprised

75% of thoracic surgery work in Guy's Hospital [3] and shortens

the waiting period before operations and thus meeting the

national guidelines for cancer therapy.[3] Better use of beds

and money saving is expected from such a project without affecting

the patient's care. There were 2 senior nurses who specialized

in thoracic surgery working in the department. They used to

look after patients with chest drains while they were in the

ward. They strongly believed that they could do the same service

in an outpatient clinic. Although no Chest Drain Clinic was

run before in UK, there were similar nurse-led projects in

NHS like chest pain and endoscopy clinics which stimulated

the Thoracic Surgery Specialist nurses to go ahead in their

project. Literature review included a few similar models in

other countries which formed a background for the project.[5]

The literature also demonstrated that outpatient management

of patients with spontaneous pneumothorax or even prolonged

air leak appeared safe, efficient and economic.[6] The nurse

specialists were further encouraged by the co-operation and

support of the consultant surgeons. Patients always preferred

to be at home as opposed to being in the hospital. The public

in UK are increasingly aware about the current roles played

by nurses in NHS. The communication system between the Senior

Case Managers, patients and Community Nurses was good enough

to support the new project beside the recent availability

of compact, self-contained, clean and more user-friendly devices

which can be strapped to the belt have been provided by manufacturing

companies. [6] Therefore there was little to worry about.

On the other hand, the nurse case managers embarking on this

change realized some potential threats to their success like

slippage of the drain after patient's discharge, inability

of the District Nurse to look after the chest drain, the clinic

might not be considered a real clinic as that run by doctors

and a minority of patients may prefer to be seen by the consultant

rather than the nurse case manager.

The skilled nurse case managers shared a future vision with

the doctors and agreed upon establishing the new clinic. They

had put a plan forward that consists of identification and

addressing the stakeholders as well as changing the systems

of discharge, follow-up and referral of patients.

The identified stakeholders were: doctors (consultant surgeons

and oncologists, GPs and juniors), patients, hospital manager,

manufacturing companies and public. All were supportive; however,

junior doctors did not make proper referrals initially.

In conclusion, out-patient care offered by nurse-led clinics

to patients with chest drain for prolonged air leak provided

many advantages over the in-patient care. The successful implementation

of the change project highlights the techniques necessary

to achieve similar changes.

References

1. Sharples L. A randomized control crossover trial of nurse

practitioner versus doctor led outpatient care in a bronchiectasis

clinic. Thorax 2002;57:661-6.

2. Moore S. Nurse led follow up and conventional follow up

in management of patients with Lung Cancer. BMJ 2002;325:1145-8.

3. The Guy's and St Thomas, NHS Foundation Trust December-2007

Newsletter.

4. The Guy's and St Thomas, NHS Foundation Trust December-2008

Newsletter.

5. Robert James Cerfolio. Closed Drainage and Drainage Systems.

In: G. Alexander Patterson et al, editors. Pearson's Thoracic

& Esophageal Surgery, Vol 1. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Churchill

Livingstone Elsevier; 2008.p.

6. Myatt R. An exploration of the patient experience following

discharge from hospital with a long term chest drain (unpublished

MSc dissertation). Imperial College, London University. 2005

|

|