| |

February

2014

- Volume 8, Issue 1

A holistic

approach to bedside teaching from the views of main users

|

((2) ((2)

|

Leili Mosalanejad

(1)

Mohsen Hojjat (2)

Morteza Gholami (3)

(1) Assistant professor,

Mental health Department, Jahrom University of Medical

Sciences, Jahrom, Iran

(2) Nursing PhD student, Nursing Department, Jahrom

University of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran

(3) English instructor, Jahrom University of Medical

Sciences, Jahrom, Iran

Correspondence:

Leila Mosalanejad

Assistant professor, Mental health Department,

Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran

Phone: 0791-3341508

Mobile: 09177920813

Email: mossla_1@yahoo.com

|

|

|

Abstract

Introduction: Clinical education concerns with

acquiring lots of skills and competencies that enable

health professionals to function properly and provide

services effectively. The aim of this study was to evaluate

a holistic examination on bedside teaching from the

views of its main users.

Materials and methods: This is a cross sectional

study on 70 teachers (clinical and nursing), 70 students

(medical and nursing), 400 patients in Jahrom University

of Medical Sciences. Data gathering tool was a three-part

questionnaire in which the first part was assigned to

demographic data, the second part was 10 five-part questions

aiming at investigating bedside teaching quality for

teachers, students, and patients. Reliability was 0.83,

0.78, and 0.89 respectively.

Results: The results showed that teachers evaluated

bedside teaching in three areas of communication skills

(50.4), proper clinical examination (44.4), and developing

professional skills (44.4) more than other fields. Sharing

some in common, the students also had a higher average

in acquisition of professional skills (83.3) enhancing

knowledge of students (82.3) and obtaining a suitable

model of communication (72.3). The patients also considered

factors such as high self-esteem, feeling of satisfaction

(3.83), humanized health care (3.83), and transfer of

information to both teachers and students (3.83) higher

than other factors.

Conclusion: According to the results, it is necessary

to appropriately train teachers to meet these standards,

and while justifying students to implement this method

and its benefits, patients' satisfaction, enhancing

health care, and effective clinical governance should

be provided.

Keywords: Bedside teaching, Teachers, Students,

Effectiveness

|

Introduction

Bedside teaching includes any kind of training in the presence

of the patient, regardless of the environment in which this

training is presented. Several studies indicated that clinical

teaching is an effective method of training and today it is

used less than in the past, but students, patients, and faculty

members strongly support this teaching method(Subha and 2003).

In this way, clinical skills related to communication between

doctor and patient, physical examination, clinical reasoning

and obtaining specific skills of professionals will be learned

better than classroom instruction methods (Williams, et al.

2008). Ramani and colleagues also expressed the benefits of

clinical teaching as communication skills, clinical examination

findings, teaching human aspects of clinical medicine and

creating conditions to model professional behavior, so that

these qualities cannot be shown effectively in the classroom

(Ramani, et al. 2003).

Furthermore, the clinical teaching provides opportunities

for teachers to observe students (EI-Bagir and Ahmed 2002)(4).

There is also evidence that suggests that these patients also

enjoy this teaching method, because they gain a better understanding

of the disease (Janick and Fletcher 2003)(5). In research

conducted by Williams Kit and colleagues on four-year medical

students and internal residents in first and second years

in medicine school at Boston University, students believed

that clinical teaching is valuable and necessary to learn

clinical skills and expressed that this method is used less

frequently and there are many obstacles in performing it,

including lack of respect to the patient, time constraints,

lack of attitude, knowledge and skills of the teachers, and

also mentioned strategies for solving these problems(Williams,

et al. 2008) (2).

Ramani and colleagues conducted a study focused on four groups

including senior assistants, skilled teachers in clinical

teaching, faculty members of hospitals affiliated to Boston

University and named the main obstacles as reduction of clinical

teaching skills, and the fear of clinical teaching. They believed

that teachers should be trained in almost all unreachable

levels of clinical diagnosis and this puts them under a lot

of pressure. They expressed that teaching is less important

than research in the universities and teaching ethics is missing.

Thus, they presented some strategies to eradicate these obstacles

including: developing clinical teaching skills by teaching

faculty members in clinical skills and teaching methods, ensuring

that teachers possess great capabilities in clinical teaching,

making a learning atmosphere to allow the teachers to accept

their limitations, and eliminate low value of teaching in

the departments with appropriate recognition and considering

rewards for the successful teachers. In the present study,

expert teachers and professors stated that the ethics of clinical

teaching must be established on emphasizing the importance

of using this method to get students to think clinically(Ramani,

et al. 2003).

Aldeen and Gisondi also conducted a study on clinical teaching

in emergency department and expressed that the emergency department

is an ideal atmosphere for clinical teaching because of high

volume of patients, high acuity and severity of diseases and

pathologies that provide a variety of patient-centered educational

opportunities(Aldeen and Gisondi 2006).

One of the major concerns of the clinical teachers is creating

a learning-teaching approach to transfer learning which occurs

in the teaching environment to the real and clinical environment.

Since interaction between medical staff and patients is considered

as an important fact in clinical work and is necessary for

treatment process and this interaction is in the presence

of the patient, therefore, research and teaching strategies

should be as close as possible to the real environment (Brien

2002). Clinical training mission is to train qualified students

with necessary knowledge, attitudes, and skills, and to achieve

this objective, standardized clinical training is an essential

component of the educational programs, since approximately

50% of the teaching programs are dedicated to clinical works

(Irma, et al. 2011). It is generally accepted that research

methods should focus on beliefs, values, and behavior of teachers

in the education system (Karimi Moonaghi et al 2010). But

in recent years, research on teaching methods and their applications

are more superficial and thus, deeper investigation is required

(Heimlich and Norland 2002) . Clinical teaching is a valuable

method used by teachers despite their relative familiarity

with it. Another notable point is failure to meet teaching

standards in implementing this method and lack of appropriate

use of it in clinical teaching. The aim of this study is to

investigate quality and effectiveness of bedside teaching

on students, teachers, and patients' points of views and determine

constraints and challenges and propose strategies to remove

them and finally, positive steps are taken to use these teaching

methods more effectively.

Materials and Methodologies

This is a cross-sectional study to investigate the effectiveness

of bedside teaching on teachers, medical students, and patients'

attitudes in the hospital affiliated to Jahrom University

of Medical Sciences. Cluster random sampling was carried out

on medical students in various fields of medical sciences

(medical and nursing students) and all nursing and clinical

faculty. Approximate number of students in the two groups

of medicine in three levels (externs - Interns) and nursing

and training courses were 70. 50 teachers of different groups

(nursing and medicine) participated in this study that performed

clinical teaching for the students. In the patients' group,

in a two-month period, all patients who were present in bedside

teaching numbered 400 and bedside teaching was carried out

on them.

Approving the research proposal and obtaining approval of

the research director, validity of the questionnaire was confirmed

according to reliable sources (1, 3, 6), and then 10 expert

professors confirmed it. Reliability in three sectors (teachers

- students and patients) was proved with Cronbach's alpha

by working on a pilot sample respectively (0.78- 0.83 and

then 0.89). The questionnaires were given to students (doctors,

nurses), patients and staff and then coded, collected, and

analyzed using SPSS statistical software. It is worth mentioning

that the questionnaires were designed by Likert method (never,

to very high, 0-4) and in addition to demographic questions,

11 more questions were included which assess the effectiveness

of clinical teaching from the viewpoints of masters, students,

and patients. Data was analyzed using descriptive statistics

such as mean, standard deviation, and Spearman and K2 test.

Inclusion criteria for the study were the interest of students,

teachers and patients to participate in the study, as well

as internship and performing bedside teaching by the teachers

and exclusion criteria included illiterate patients, patients

with somatic and psychiatric disability, patients in critical

units because of the lack of accountability, patients where

this method was not determined in their wards and patients

in ambulatory wards.

Results

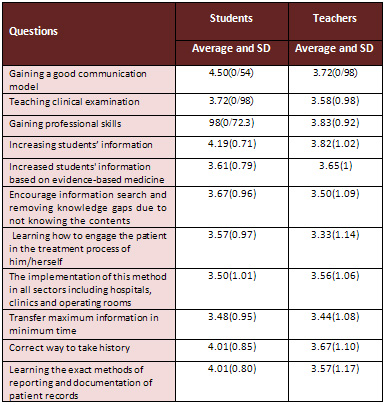

The results showed that the pattern of acquisition of good

communication, training, performing physical exam, gaining

professional skills and increased general information have

a higher average. From the students' views, gaining professional

skills and increasing students' general information and obtaining

appropriate communicative plans have higher average.

Table 1: Mean score of bedside

teaching quality from the perspective of both teachers and

students

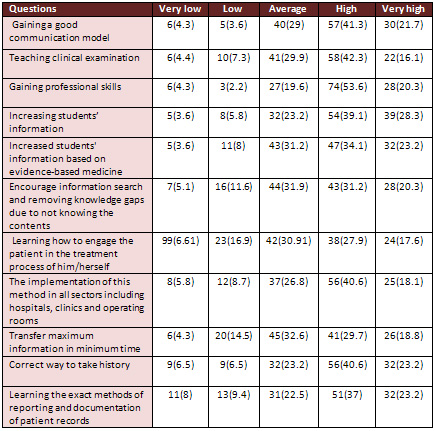

Table 2 shows that most students considered the quality of

bedside teaching from moderate to high.

Table 2: Descriptive statistics

of the effectiveness of bedside teaching from students' views

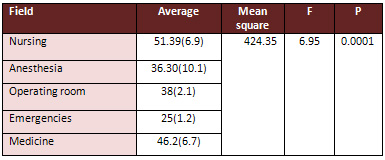

Additional

results showed that there is a significant relationship between

the effectiveness of bedside teaching and field of study (02/0

P = ,60/17 X2). But there is no relationship between age,

sex, and method effectiveness. There is a significant relationship

between viewpoints of both sexes on the effectiveness of bedside

teaching (T= 3/87, P= 0.02). Other results showed that there

is a significant difference among students in terms of fields

of study.

Table 3: Mean differences in terms of effectiveness of

bedside teaching based on field of study

Additional results related to the

effectiveness of this method indicated that the majority of

patients were in the age groups 60-51 years (25.3%) and the

majority with 43.3% in wards, 52% men's internal ward, and

48% women's ward, and majority had primary education.

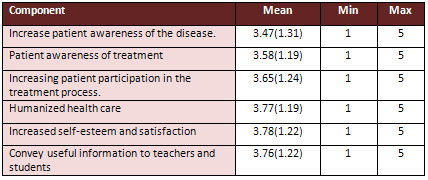

Table 4 shows that this method is most effective in raising

self-esteem and feelings of patient satisfaction and cause

medical care to become humanistic and useful information passes

to students and the teachers.

Table 4: Mean of effectiveness

on bedside teaching from the patients' views

59.9% of the patients evaluated the bedside teaching as high

and very high, 26.5% average, and only 3.3% low and very low.

Other results showed that the quality and effectiveness of

this method are high, and very high from the viewpoints of

patients. Other results showed that there is a significant

relationship between age and education in terms of correlation

between age and effectiveness of bedside teaching (p= 0.008,

r= 0.15).

But there is no significant relationship between the effectiveness

of bedside teaching in terms of sex, kind of disease, the

ward, and the education.

Other results indicated that there is a significant relationship

between patients' viewpoints of effectiveness of bedside teaching

based on age (F=2.47, P=0.03). But as other cases show, it

is suggested that the effectiveness of the method based on

demographic variables was not significant.

Table 5: Difference of bedside

teaching effectiveness based on demographic variables

Discussion

The results show that obtaining a good communicative pattern,

appropriate teaching, clinical examination, acquisition of

professional skills and increasing students' scientific information

on the viewpoints of teachers have a higher average.

In another study conducted to investigate the experiences

of advisor faculties and fourth-year students of medicine

in a qualitative study on bedside teaching of medical students

and advisor faculties, advisor faculties were under pressure

considering time spent over other commitments, despite enjoying

this approach. The results showed that all of the teaching

strategies used by the teachers were not welcomed with great

enthusiasm by the students. Students considered the teachers

as an educational model (Stark 2003a).

In a study conducted by Celenza, Rogers, with the aim of investigating

the effectiveness of bedside teaching on patient care with

a 6-month perspective study in emergency department, people

stated that the most common lesson they took from this method

was skills in history taking and physical examination and

cited clinical reasoning as the most important lessons learned

from this approach(Celenza and Rogers 2006).

Studies conducted by Gonzalo et al on 51 local residents and

102 medical students from educational rounds and bedside teaching

revealed that time spent in clinical practice for the learners

to learn bedside teaching is very important for professional

development and that this method is preferred by the learners

compared with other methods of bedside teaching training (Gonzalo,

et al. 2009).

In another study, hospitalists spent an average of 101 minutes

on teaching rounds and an average of 17 minutes inside patient

rooms or 17% of their teaching time at the bedside. This study

showed rounds that included time spent at the bedside were

longer on average than rounds that did not include time spent

at the bedside(Crumlish, et al. 2009).

In research conducted on 27 patient attendants, 22 patients,

and 21 residents, the attendants expressed their satisfaction

with bedside teaching and presented a case report in a conference

room in a linear range. 96 versus 92 out of 100 linear parts,

expressed their preferences with bedside teaching (95 vs.

15), and comfort (89 vs. 19) in this range. But there was

no significant difference in residents' satisfaction and comfort

in applying this method. These people were more comfortable

in asking questions (84 vs. 69), having the art of asking

questions (85 vs. 67) in the conference room. This study showed

that 81% of patients' attendants wished that the next examination

was with their patient.

Evidence shows that bedside teaching includes 61% of clinical

training and performed examinations. This method takes more

time than the typical round (Landry, et al. 2007).

A study conducted to evaluate this educational method and

its impacts on the attitudes of students and patients, revealed

that although there is a slight difference among some students,

to present the contents away from the patient's bedside, students

expressed that students learned more about diagnosing and

staying by the patients' bedside at the time of bedside teaching.

But students' knowledge of mechanism of diseases was lower

than presentation out of clinical wards(Rogers, et al. 2003).

In a study conducted on 108 patients and 142 fourth-year medical

students at Washington University, students and patients preferred

bedside teaching as a teaching method; patients more easily

communicate with doctors and talked about their health issues.

Also, two groups of patients and

students benefited more from participating in bedside teaching

(17).

In another study aiming at examining viewpoints of internal

residents and medical students, it became clear that this

approach is effective in developing skills such as history

taking 55%, physical examination skills (89%) professional

72%, physician-patient communication skills 83%, differential

diagnosis 43%, and patients' management 59% (Jed, et al. 2009).

Some evidence states that outcome of this method is dependent

on 1) the value of peer assessment in a group , (2) variety

of teaching strategies, (3) the opportunities to provide feedback

to learners, (4) the art of asking questions effectively,

and (5) the possible relationship between a teacher's skills

and successful bedside teaching (Beckman 2004).

In another study the importance of peer assessment was investigated

and the benefits such as high value of using peer assessment,

applying an unlimited number of teaching strategies, applying

this method to revive missed opportunities, the art of asking

question effectively, and the relationship of teacher maturity

and bedside teaching were emphasized. The results of this

study are the same with the abovementioned results considering

bedside teaching approach so that the development of communication

skills, performing proper clinical examination, and improvement

of professional skills, were expressed as the most important

results regarding the quality of this method.

The results also showed that all of the teaching strategies

used by teachers in this method may not be welcomed by the

students. And, despite the fact that students and teachers

are partners in education, general agreement about the quality,

quantity and clinical teaching may fail to be materialized

considering appropriate clinical teaching(Stark 2003b).

In the present study, despite acceptable reported quality

of bedside teaching and its clinical aspects (moderate to

high) which indicates the relative familiarity and acceptable

application of this educational method, lack of time is considered

as an obstacle to applying this technique.

The positive effects of this method can be noted as numerous

roles of the clinical teachers including, actor, director,

audience, passive, and listener. Also, in presenting this

method, the patients undergo less passive roles and mere audience

(Lynn 2009). This can justify the obtained results regarding

patients' satisfaction and their consent to participate in

this educational method.

Also, the positive effects of this method on patients' participation

in health care plans and changing their positions due to participation

can be noted as an advantage of this method. However, no negative

impact on patients' care was found. The results of this study

are consistent with the results presented in the following

study (Celenza and Rogers 2006).

Other advantages of this method may include opportunities

to gather additional information, direct observation of learners'

performance, humanizing care for patients, non-judgmental

language, improving patients understanding of their disease

and feeling active on the side of patient(Janicik and Fletcher

203). All of these outcomes justify patient satisfaction with

the use of this method.

Given the quality of the bedside teaching provided by main

users of this educational method, it is necessary to consider

different approaches and strategies such as clinical skills,

teaching methodologies by the teachers, ensuring the application

of this method aiming at understanding these points to rely

on their knowledge and skills, creating a learning environment

that allows teachers to become aware of their limitations

and examine their capabilities, sufficient reward for the

efforts of the teachers, and emphasis on the revival of ethics

in bedside teaching (Ramani, et al. 2003).

Among other strategies to reduce barriers examining the clinical

setting, are addressing time constraints by adopting a flexible

training program, proper patient selection, ensuring the learners,

improve learner autonomy in the teaching process, and developing

evidence-based education. (Keith, et al. 2008).

Conclusion

Considering the importance of bedside teaching method and

regarding the good views of the teachers, patients, and middle

and high students' views, it is necessary to provide training

classes to develop teachers' capabilities, justify the students

and mention its benefits, and to pave the way to use this

method appropriately. Also, using this method considering

the positive and appropriate patients' views, can provide

a holistic analysis of health care and improve health and

to provide effective implementation of clinical governance.

Acknowledgement:

This study is the result of a research plan approved by Jahrom

University of Medical Sciences. Hereby we would like to express

sincere gratitude to the research assistant of the university

for financial support.

References

1. Subha R. Twelve tips to improve bedside teaching. Medical

Teacher, ,2003 ;25( 2): 112 - 115.

2. Williams K, Rammani S, Fraser B, Orlander JD. Improving

Bedside Teaching: Findings from a Focus Group study of learners.

Acad med 2008 ; 83: 257-264.

3. Ramani S, Orlander JD, Strunin L, Barber TW. Whither bedside

teaching? A focus group study of clinical teachers. Acad med

2003; 78: 384-390.

4. EI-Bagir M, Ahmed K. What is happening to bedside clinical

teaching? Med Educ 2002; 36: 1185-1188.

5. Janicik RW, Fletcher

KE. Teaching at the bedside: a new model. Med Teach 2003;

25 (2): 127 - 130 .

6. Aldeen AZ, Gisondi

MA. Bedside Teaching in the Emergency Department. Acad Emerg

Med. 2006 Aug;13(8):860-6.

7. Brien RO. An overview

of the Methodological Approach of Action Research. 2002. Available

from: http: // www. Web.Net/~robrien/ papers/ arfinal.html

8-. Irma H. Mahone ,

Sarah P. Farrell ,Ivora Hinton , Robert Johnson ,et.al. Participatory

Action Research in Public Mental Health and school of Nursing:

Qualitative findings from an Academic - community partnership.

Journal of Participatory Medicine; 2011 ,3.

9. KarimiMoonaghi H ,Dabbaghi

F ,Oskouieseid F ,Vehvilainen-Julkunen K.I. Binaghi T Teaching

style in clinical nursing education: A qualitative study of

Iranian nursing teacher's experiences. Nurse Education in

Practice 2010; 10: 8-12.

10. Heimlich J E. , Norland E. , 2002. Teaching style: where

are we now? New Directions for adult and continuing Education

93 , 17- 25.

11. Stark P. Teaching

and learning in the clinical setting: a qualitative study

of the perceptions of students and teachers. Medical Education

2003;37(11):975-982.

12. Celenza A , Rogers

IR. Qualitative evaluation of a formal bedside clinical teaching

programme in an emergency department. Emerg Med J 2006;23:769-773

.

13. Gonzalo JD , Masters PA Simons RJ , Chuang CH. Attending

rounds and bedside case presentations: medical student and

medicine resident experiences and attitudes. Teaching and

Learning in Medicine 2009;21(2):105-10.

14. Landry MA , Lafrenaye

S , Roy MC , Claude Cyr C. A Randomized ,Controlled Trial

of Bedside Versus Conference-Room Case Presentation in a Pediatric

Intensive Care Unit. Pediatrics 2007;120;275-280

15.C rumlish C M ,Yialamas

M A ,McMahon G T. Quantification of bedside teaching by an

academic hospitalist group. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2009;4(5):

304-307.

16. Rogers HD , Carline

JD , Paauw DS. Examination room presentations in general internal

medicine clinic: patients' and students' perceptions. Acad

Med. 2003 Sep;78(9):945-9.

17. Rogers HD Carline

JD , Paauw DS. Examination room presentations in general internal

medicine clinic: patients' and students' perceptions. Acad

Med. 2003 Sep;78(9):945-9.

18. Jed D. Gonzalo ,Philip

A. Masters and Richard J. Simons, Cynthia H. Chuang. Attending

Rounds and Bedside Case Presentations: Medical Student and

Medicine Resident Experiences and Attitudes. Teach Learn Med.

2009; 21(2): 105-110.

19. Beckman T J. Lessons Learned

from A Peer Review of Bedside Teaching. Academic Medicine

2004; 79(4): 343-346.

20. Stark P. Teaching and learning

in the clinical setting: a qualitative study of the perceptions

of students and teachers. Medical Education 2003;37(11):975-982.

21. Lynn V. Monrouxe

. The Construction of Patients' Involvement in (Attewell 2006)

Hospital Bedside Teaching Encounters. Qual Health Res July

2009 ; 19 (7): 918-930.

22. Celenza A, Rogers IR. Qualitative

evaluation of a formal bedside clinical teaching programme

in an emergency department. Emerg Med J 2006;23:769-773 .

23. Janick WR ,Fletcher

KE. Teaching at the bedside: a new model. Medical Teacher

2003; 25( 2) : 127-130 .

24. Keith N W, Subha R, Bruce

F , Jay D O. Improving Bedside Teaching: Findings from a Focus

Group Study of Learners. Academic Medicine 2008 ; 83 ( 3 ):

257-264

Further

reading

Aldeen, A.Z., and M.A. Gisondi. 2006 Bedside Teaching in the

Emergency Department. 2006; by the society for academic Emergency

medicine doi: 10. 1197/J.aem. 2006. 03. 557. Acad Emerg Med

13(8):860-6.

Attewell, J. 2006 From research and development to mobile

learning: Tools for education and training providers and their

learner. The International Review of Research in Open and

Distance Learning 7(3):Available from www.irrodl.org.

Beckman, T .J. 2004 Lessons Learned from A Peer Review of

Bedside Teaching. Academic Medicine. 79(4):343-346.

Brien, R.O. 2002 An overview of the Methodological Approach

of Action Research. Available from: http: // www. Web.Net/~robrien/

papers/ arfinal.html.

Celenza, A., and I.R. Rogers 2006 Qualitative evaluation of

a formal bedside clinical teaching programme in an emergency

department. . Emerg Med J 23.:769-773

Crumlish, C. M., M. A. Yialamas, and G.T. McMahon 2009 Quantification

of bedside teaching by an academic hospitalist group. Journal

of Hospital Medicine 4(5):304-307.

EI-Bagir, M., and K. Ahmed 2002 What is happening to bedside

clinical teaching? . Med Educ 36:1185-1188.

Gonzalo, J.D., et al. 2009 Attending rounds and bedside case

presentations: medical student and medicine resident experiences

and attitudes. Teaching and Learning in Medicine 21(2):105-10.

Heimlich , J.E. , and E. Norland 2002 Teaching style: where

are we now? New Directions for adult and continuing Education

93: 17- 25.

Irma, H. M., et al. 2011 Participatory Action Research in

Public Mental Health and school of Nursing: Qualitative findings

from an Academic - community partnership. Journal of Participatory

Medicine 3.

Janicik, R.W ., and K.E. Fletcher 203 Teaching at the bedside:

a new model. Med Teach 25(2):127-130.

Janick, W.R., and K.E Fletcher. 2003 Teaching at the bedside:

a new model. . Medical Teacher 25 ( 2):127-130

Jed, D. G, et al. 2009 Attending Rounds and Bedside Case Presentations:

Medical Student and Medicine Resident Experiences and Attitudes.

Teach Learn Med. 21(2):105-110.

KarimiMoonaghi, H., et al. 2010 Teaching style in clinical

nursing education: A qualitative study of Iranian nursing

teacher's experiences. Nurse Education in Practice 10:8-12.

Keith, N.W., et al. 2008 Improving Bedside Teaching: Findings

from a Focus Group Study of Learners. Academic Medicine .

83(3):257-264.

Landry, M.A., et al. 2007 A Randomized Controlled Trial of

Bedside Versus Conference-Room Case Presentation in a Pediatric

Intensive Care Unit. Pediatrics 120:275-280.

Lynn, V. M. 2009 The Construction of Patients' Involvement

in Hospital Bedside Teaching Encounters. Qual Health Res 19(7):918-930.

Ramani, S., et al. 2003 Whither bedside teaching? A focus

group study of clinical teachers. . Acad med 78: 384-390.

Rogers, H.D., J.D. Carline, and D.S. Paauw 2003 Examination

room presentations in general internal medicine clinic: patients'

and students' perceptions. Acad Med.. 78(9):945-9.

Stark, P. 2003a Teaching and learning in the clinical setting:

a qualitative study of the perceptions of students and teachers.

Medical Education 37(11):975-982. 2003b Teaching and learning

in the clinical setting: a qualitative study of the perceptions

of students and teachers. Medical Education. 37(11):975-982.

Subha, R., 2003 Twelve tips to improve bedside teaching. Medical

Teacher 25( 2):112 - 115.

Williams, K., et al. 2008 Improving Bedside Teaching: Findings

from a Focus Group study of learners. Acad med 83:257-264.

|

|