| |

June

2014

- Volume 8, Issue 3

Phases of Therapeutic

relationship Implementation among the Queen Alia Heart Center

Nurses

|

( (

|

Ala'a AL-A'araj

Ahmad AL- Omari

Correspondence:

Ahmad Kamel AL-Omari

Instructor & Faculty Member, Royal Medical Services

College for Allied Health Professions, Department of

Nursing

Jordanian Royal Medical Services

PO box. 36033 , Alhashmy Aljanoubi , Amman , Jordan

11120

Telephone: 00962772080776

Email: ahmadalomari85@hotmail.com

|

|

Introduction

Achieving a relationship of mutual trust and respect between

the nurse and the patient requires the ability to communicate

a sincere interest in the patient (1). The therapeutic relationship

is purposeful and goal oriented, which creates a beneficial

outcome for the patient (2+3), unlike the social relationship,

where there may not be a specific purpose or direction (11+12).

In fact, for interventions to be successful with clients in

all nursing specialties, it is crucial to build a therapeutic

relationship. So, crucial phases are involved in establishing

a therapeutic nurse-patient relationship and the communication

within it which serves as the underpinning for treatment and

success (2+4+10).

The concept of therapeutic relationship

is used in many disciplines and is recognized as one of the

important concepts in nursing (2+3+4+6+9). In the practice,

the therapeutic relationship can be described in terms of

four sequential phases, each characterized by identifiable

tasks and skills, and theses phases are: preinteraction phase,

introduction phase, working phase, and termination phase (2+4+5).

So, the therapeutic relationship must progress through the

stages in succession because each builds on the one before.

In fact, even though most healthcare professionals, including

nurses, know the phases and its skills very well, they have

trouble applying them to their behaviors, particularly in

hospitals where there are a huge number of patients in comparison

with small number of nurses assigned to the patients (3+5+6+7+8).

This gap between the therapeutic

relationship perception and the therapeutic relationship practice

directs us toward this study (5+11+12). So, the purpose of

this study is to assess the current practices and problems

that are encountered regarding the implementation of therapeutic

relationship phases among registered nurses at Queen Alia

Heart Center.

Methodology

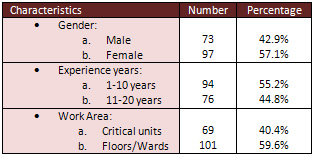

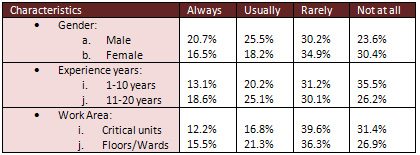

The descriptive design was used for this study. A convenience

sample of 200 registered nurses was selected from both genders

with different experiences, who were working in the wards

and units of the Queen Alia Heart Center (Table 1).

Table 1: The characteristics of the sample

A questionnaire was developed by the researchers and consists

of 25 statements that assessed the implementation of the therapeutic

relationship phases by nurses, in addition to the barriers

for providing the phases according to the nurses. The four

point's Likert scale questionnaire was reviewed by an expert

panel consisting of nurse educator, nurse administrator and

senior nurse colleague to establish its content validity.

The stability reliability was checked by administering the

questionnaire to a group of 40 registered nurses selected

conveniently from both genders with different experiences.

Then after 3 weeks, the same instrument was administered to

the same group. The correlation coefficients were calculated,

and it was equal to (+0.83).

The data collection was carried out on 21 st of July 2013.

The response rate was 85% (n=170).

Results

The therapeutic relationship in our study was divided

into four sequential phases: preinteraction phase, introduction

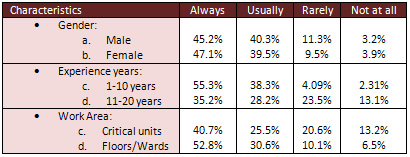

phase, working phase, and termination phase. The preinteraction

phase involves preparation for the first encounter with the

client, which includes obtaining available information about

the client from the available sources; like their file, family,

and other health team members(2+4+5). The preinteraction phase

also includes examining the client's feeling, fears, and anxieties

before the interaction with the client(10). In our study,

the majority of the nurses either always (46%) or usually

(40.1%) practice the preinteraction phase during their encounter

with their clients, while (10.3%) rarely do it, and (3.6%)

not at all. (Table 2)

Table 2: The results of preinteraction phase

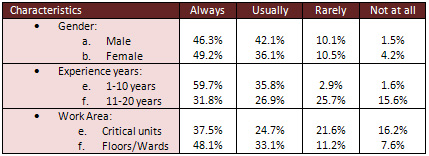

The second phase of the therapeutic relationship is the introduction

phase. During this phase, the nurse and client become acquainted

(2). This phase includes creating an environment for establishment

of trust and rapport, identifying the client's strength and

limitations, and exploring feelings of both client and nurse

(2+4+5). The introduction phase also includes formulating

nursing diagnosis, setting mutually agreeable goals, in addition

to developing a realistic plan of action to meet the established

goals (4+5+9). In our study, almost three quarters of the

nurses stated that they were either always (32.4%) or usually

(38.5%) practicing the introduction phase of the therapeutic

relationship, while (20.1%) rarely did it, and (9% ) not at

all. (Table 3)

Table 3: The results of introduction phase

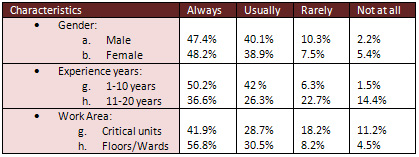

The third phase of the therapeutic relationship is the working

phase, in which the therapeutic work of the relationship is

accomplished (4+7+9). This phase includes problem solving

and overcoming client's resistance, in addition to maintaining

the trust and rapport that was established during the introduction

phase (2+5). The working phase also includes continuously

evaluating progress toward goal attainment by using direct

and purposeful questions during the interaction with the client,

while keeping eye contact with them (4). In our study, the

majority of the sample either always (32.8%) or usually (41.8%)

practice the working phase of therapeutic relationship, while

(19.7%) of the nurses stated that they did it rarely and (5.6%)

not practicing it at all. (Table 4).

Table 4: The results of working phase

The fourth and last stage is the termination phase, in which

therapeutic conclusions were brought to the communication

and relationship with the client (2+4). This phase includes

attaining of mutually agreed-on goals and setting a plan for

continuing care, in addition to providing health education

according to the client's needs(5). In our study, just one

third of the nurses were either always (13.8%) or usually

(21.2%) practicing the termination phase, while (35.8%) rarely

did and (29.2%) were not practicing the termination phase

at all. (Table 5).

Table 5: The results of termination phase

On the other hand, in response to a question about the biggest

perceived barrier to practicing therapeutic relationship phases

with their clients; 40% of the nurses think that the most

common barrier is gender differences, while 35.4% of the nurses

think that the nursing shortage and educational background

differences are considered as barriers for the practicing

of the therapeutic relationship phases.

Discussion

Although each phase of the therapeutic relationship is

presented as specific and distinct from each other, there

may be some overlapping of tasks, particularly when the interaction

is limited (4). Even then, there are major tasks and goals

during each phase and the client-nurse relationship must progress

through these phases in succession. So, nurses must identify

and practice these phases to build a healthy therapeutic relationship

with their clients.

In our study, the preinteraction phase, introduction phase,

and working phase were practiced always and usually by the

majority (more than 65%) of the participants, while, the termination

phase was practiced always and usually by just about one third

(35%) of the participants. The small percentage of practicing

the termination phase by the participants in comparison with

the other phases reflects the high need to train nurses about

how to practice the phases of therapeutic relationship, because

the therapeutic relationship must progress through the phases

in succession to build a healthy relationship with the clients.

The termination phase is often expected to be difficult and

filled with ambivalence (2+4), which could be caused by the

feeling of sadness and loss that may be experienced by both

the nurse and the client. However, if the previous phases

have evolved effectively, the client generally has a positive

outlook and feels able to handle problems independently (5).

The results of our study also show that both male and female

participants practice the first three phases of therapeutic

relationship in almost the same percentage, but on the other

hand, the male participants practice the termination phase

more than female participants. This could be caused by the

nature of warm emotions that females have more than males.

In related to years of experience, the results show that the

less experienced nurses (1-10 years) practice the first three

phases of therapeutic communication more than the highly experienced

nurses (11-20 years), which may be because the less experienced

nurses are more restricted by the rules of the hospital, and

their knowledge is fresher than the highly experienced nurses.

In contrast, the results show that termination phases are

practiced by highly experienced nurses more than the less

experienced nurses, because the termination phase is more

difficult to practice than the other phases and needs more

experience in dealing with and building relationships with

clients.

In addition, the results show that the phases of therapeutic

relationship are more practiced in the general floors/wards

than the critical units, which may be caused mostly by the

fact that the consciousness and orientation status of clients

in the critical units are lower than in general floors/wards.

Indeed, consciousness and orientation status of the clients

is considered as an integral element of nurse-client interactions

to build the therapeutic relationship (3).

Furthermore, the barriers of practicing the therapeutic relationship

by nurses in our study were mainly the gender differences

between the nurse and the client, then by the huge workload

that is caused by nursing shortage. In the previous studies,

the barriers were mainly the nursing shortage (4+6+7).

Conclusion and Recommendations

The therapeutic relationship is the foundation on which

nursing care is delivered. So, nurses who practice therapeutic

relationships effectively are better able to initiate change

that promote the health, establish trust relationship with

the patient, and prevent legal problems associated with the

nursing practice. Healthcare institutions must provide effective

training to enhance the therapeutic relationship. Indeed,

we hope that the hospitals will heed the call to improve discretion

for the patients who entrust us with their care.

References

1. Smeltzer, S., & Bare, B. (2003). Brunner and Suddarth's

textbook of medical-surgical nursing (10th edition). Philadelphia:

Lippincott. Chapter 3.pages (35-38).

2. Kozier, B., & Erb, G. (2004). Fundamentals of nursing

(7th edition). New Jersey: Pearson Education. Chapter 24.

Pages (428-442).

3. Annells M. (1996) Hermeneutic phenomenology: philosophical

perspectives and current use in nursing research. Journal

of Advanced Nursing 23, 705-713.

4. Tousand, M. (2005). Essentials of psychiatric mental health

nursing (3rd edition). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company. Unit

2, chapter 5. Pages (73-83).

5. Brammer, L.M. (1998). The helping relationship: Process

and skills (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

6. Bickley, L. S., & Hoekelman, R. A (1999). Bates' guide

to physical examination and history taking (7th ed.). Philadelphia:

Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

7. Day, L. J. , & Standard, D. (2006). Developing trust

and connection with patients and their families. Critical

Care Nurse, 19(3), 66-70.

8. Peplau, H.E. (1991). Interpersonal relations in nursing.

New York Springer

9. Raskin, N.J., & Rogers, C.R. (1995). Person- centered

therapy.

10. Adam O. Horvath. The therapeutic relationship: Research

and theory. Psychotherapy Research. Volume 15, Issue 1-2,

2005. pages 3-7

11. Fiedler, Fred E. A comparison of therapeutic relationships

in psychoanalytic, nondirective and Adlerian therapy. Journal

of Consulting Psychology, Vol 14(6), Dec 1950, 436-445.

12. Saltzman, C.; Luctgert, M. J.; Roth, C. H.; Creaser, J.;

Howard, L. Formation of a therapeutic relationship: Experiences

during the initial phase of psychotherapy as predictors of

treatment duration and outcome. Journal of Consulting and

Clinical Psychology, Vol 44(4), Aug 1976, 546-555.

|

|