| |

March

2016

- Volume 10, Issue 1

What women have to say about giving birth in Saudi Arabia

|

( (

|

Ibtesam

Jahlan (1)

Virginia Plummer (2)

Meredith McIntyre (3)

Salma Moawed (4)

(1) Ibtesam

Jahlan

PhD candidate

MCM RN RM

Monash University/ King Saud University

(2) Plummer, V.,

Associate Professor Nursing Research

RN PhD FACN FACHSM

Monash University

(3) McIntyre, M.,

Director of Education

Coordinator Master of Clinical Midwifery

PhD MEdSt B.AppSc RN RM

Monash University

(4) Moawed, S. Prof. Dr. Salma Moawed

Professor of Maternity & Gynaecological Nursing,

Ph. D., M.Sc.N., B.Sc.N.

King Saud University

Correspondence:

Ibtesam Jahlan

Monash University/King Saud University

Telephone: +61 0421 448 127

Email: ibtesam.o.j@gmail.com

|

|

|

Abstract

Background: Reporting the voices of women giving

birth in KSA in order to inform policy developments

within the Saudi maternity healthcare system is important

to understand what the women want from the service and

how to improve it.

Aim: to explore current birthing services in

KSA from care consumers' perspectives by reporting women's

birthing experiences and voices.

Methods: Within the first 24 hours after giving

birth in one of the three selected public hospitals,

169 women shared their birth experience through their

responses to an open-ended question on a questionnaire

or by contributing in one-to one conversation with the

researcher.

Findings: Thematically analysing 169 written

responses and notes for conversation have produced two

main categories which include themes and a number of

sub-themes. The first and major category is "The

relationship between women and care providers during

birth" which is considered by most women the leading

cause for better and satisfied birth experience if this

relationship is characterised by support, respect, trust,

and empowerment. The second category is "Hospital

rules and policies and childbirth experience" especially

if these policies restrict women's choices and are brought

into action without full explanation to women about

why these policies are active.

Conclusion: Maternity care policy makers in Saudi

Arabia have to consider women's voices in building and

reviewing maternity policies and focus on empowering

childbearing women and ensuring safe motherhood.

Key words: Childbirth,

Maternity services in Saudi Arabia

|

1. Introduction

and Literature Review

Maternity services in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA)

have been classed by the World Health Organization (WHO) as

comparable with developing countries (1), concurrently, health

services in KSA are experiencing rapid modernization, economic

growth and diversity (2). Maternity services are also being

influenced by these changes. In order to inform policy developments

within the Saudi maternity healthcare system as part of the

modernisation process it is important to understand what the

women giving birth in KSA say about maternity services.

Australia was one of the first countries to conduct reviews

of maternity services inviting submissions from women who

have been consumers of those services. The review sought women's

opinions, experience and degree of satisfaction experienced

with the model of maternity care they received (3-7). Globally,

scholars used women's birthing experience and their voices

to reflect on maternity services. In Scotland, Sweden, Finland

and the USA, reviews for maternity services were undertaken

by exploring women's and/or health care providers' and policy

makers' views about their experiences within the current maternity

care system (8-11). It was suggested that more effort is required

to improve the information provided to women and the choices

available for women regarding the care they receive during

pregnancy and birth (9). Trusting the system was found to

be a major issue for those women who sought non medicalised

care (10). Women reported feeling dissatisfied with the care

they received despite the fact that they were deemed to have

been provided quality care, as measured by the low perinatal

mortality rates. Lack of choice and loss of personal autonomy

in decision making regarding the care they received was reported

as a major source of dissatisfaction (12, 13).

Maternity research in the Middle East region has been focused

on reporting a number of clinical outcomes such as maternal

and perinatal mortality and morbidity and common birthing

practices in line with the medicalization of birth to reflect

on the quality of the maternity services in these countries.

A number of studies were conducted in Jordan and were considered

to be among the first of their kind in the Middle East reporting

women's childbirth experience. These studies show women's

negative childbirth experience using different quantitative

and qualitative methodologies (14, 15) (16). The lack of inclusion

of women's personal experiences of maternity services evidences

a gap in the literature resulting in limitation of maternity

services review findings for the Middle East area.

The voices of Middle Eastern women until now have been silent

and unreported, excluded from policy decisions related to

quality of maternity care improvement. This situation is at

odds with maternity services reviews and research findings

globally, that sought the views of women, the key stakeholders

of the service when it comes to the quality and safety of

maternity services (11, 12, 16, 17).

This study reports Saudi women's experiences of the maternity

care they received, viewed through the lens of safe motherhood

to provide these women's voices with the opportunity to be

heard and in doing so potentially influence maternity service

policy developments in KSA.

2. Methods

2.1 Research design

This study is part of a large mixed method study that explored

birthing services in KSA from two perspectives, women and

health care professionals. Data was collected using the survey

and interviews techniques to describe birthing services in

Saudi Arabia and how these are viewed by women and maternity

health care providers. This paper addresses the findings of

the qualitative section of the study related to the women,

as consumers of maternity care.

2.2 Study sites and participants

This study took place in three specialised maternity hospitals

located in three main cities in Saudi Arabia; Jeddah, Riyadh,

Ad Dammam. The number of births in each hospital is approximately

6000 births/ year (18). One of the three hospitals has achieved

JCA international accreditation, and offers additional services

to those offered by the other two hospitals and consequently

experiences a strong demand by mothers seeking to give birth

in this hospital. For example, the hospital that had JCA accreditation

provides breast feeding classes and consultation through a

breast feeding specialised clinic which is run by breastfeeding

specialist. The other two hospitals provide routine maternity

care. Ethical approval to conduct the research was obtained

from Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee after

the approval was gained from the three individual participating

maternity hospitals in KSA.

2.3 Data collection

One hundred and thirty seven women shared their experiences

related to the maternity care they received, in response to

an open-ended question on a questionnaire. The questionnaire

results are reported elsewhere.

'Apart from meeting your new baby, and knowing that your baby

had no serious health concerns, and apart from the pain you

had during labour and birth, what was the best and the worse

thing about your recent experience of giving birth?'. The

questionnaires were distributed to all eligible women giving

birth in one of the selected hospitals. Participating women

were aged over 18 years, able to read and write Arabic language,

had given birth within the previous 24 hours and cleared for

discharge from hospital after giving birth to a single / multiple

babies (Table 1). The questionnaires were collected in a designated

sealed box at the reception desk in each ward. In addition,

32 of the participating women joined the study through one-to-one

conversation about their last childbirth experience with the

researcher, which was initiated during the distribution and

collection of the questionnaires in the hospital wards. Those

women either were unable or did not wish to write down their

experiences, but wanted to participate in the study. Those

women enjoyed having the opportunity to join the conversations

to share their birth experiences especially when these conversations

took place in a post-natal shared room. Within Saudi culture,

women enjoy speaking to other women of their birthing experiences

as part of an informal debriefing process providing opportunity

to express feelings and fears. This unplanned outcome of this

study (female conversations) enriched the qualitative data

findings with the researcher notes that were written immediately

after each conversation.

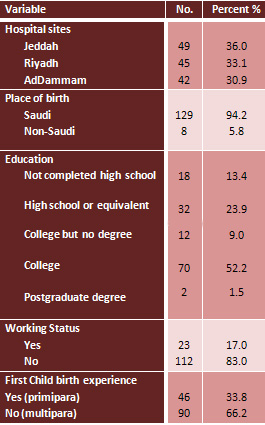

Table 1: Participants' Demographics

2.4 Data Analysis

All women's answers for open-ended question and researcher

notes for women's quotes were recorded in Arabic requiring

the data to be translated into English. Following translation

thematic analysis was used to discover patterns hidden within

the texts (19). Thematic analysis began with preparing the

data by transcribing, translating and organizing the documents.

Then the data was explored through reading and re-reading

to a point where the researcher felt totally integrated and

familiar with the participants` words. After that, the researcher

generated initial codes and searched for themes by grouping

the similar descriptions and expressions coded until themes

emerged. Next, the data analysis findings were validated by

reviewing the themes with other research and repeatedly reflecting

to ensure there was no missed classification and that the

identified themes were valid representations of the participants`

perceptions. The final steps were presenting the data analysis

and producing the findings report, wherein the resulting themes

were identified and described using the participants` words

and comments (19, 20).

Rigor was maintained using the golden criteria of trustworthiness

for qualitative research outlined by Guba and Lincoln (21),

which has been applied widely for ensuring the rigor in most

qualitative studies. The criteria, including credibility,

dependability, confirmability and transferability were attained

through reporting the findings by supporting each theme with

women's own words and commentary reflecting women's voices

clearly through each theme. Moreover, sufficient description

for the sample, data collection and analysis is provided for

any possible transferability (22).

3. Results

Thematically analysing women's written responses provided

through returned questionnaires and researcher's notes for

woman-to-woman conversations resulted in a variety of women's

comments that reflect the approach of maternity care delivered

in each hospital. Two main categories of comments evolved

from the data collected regarding what women believed was

the best and the worse things that happened to them during

their experiences of maternity care. A variety of themes and

subthemes have been reported within these two categories.

The extracted categories and themes represent women's childbirth

experience in Saudi Arabia. The first and major category is

"the relationship between woman and care providers".

The second category is 'hospital rules and policies and the

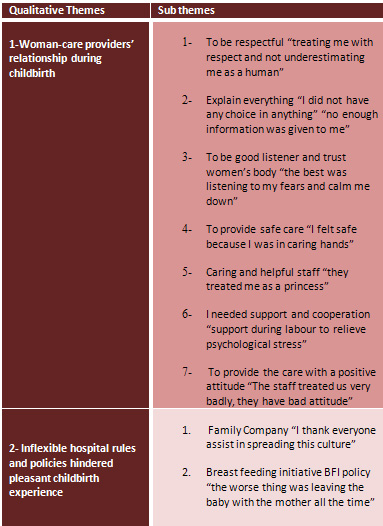

childbirth experience'. (Table 2)

Table 2

3.1 The relationship between women and care providers during

childbirth

The relationship between women and care provider is one of

medical domination in Saudi Arabian maternity services where

women are expected to leave all important decisions to the

staff (nurses and doctors) as they are perceived to know best.

The first common experience reported by women relates to the

maternity care providers' support and attitude towards the

women and their respect and interactions with the women. This

category has been divided into seven themes.

3.1.1 To be respectful "treating

me with respect and not underestimating me as a human":

A number of mothers reported appreciation of the staff who

treated them respectfully:

P23: "In the labour and

delivery room the staff treated me very well and with respect.

P134: "the best thing was

treating me with respect and humanity and not underestimating

me as a human".

Conversely, women who were treated with disrespect during

their birth experience expressed their unpleasant feelings

in their words.

P6: "The worse thing was

ignoring me…and not respecting my psychological condition

during labour".

P300: "I felt the difference

between the treatment of the nurse who treats with more respect

than the consultant did."

Similarly, a number of women described feeling embarrassed

by some staff actions that they considered as disrespectful

and humiliating:

P189: "the worse thing

was that during suturing time after birth, the situation was

bad as the Dr.(F) and complete medical team were in the room

which embarrassed me."

C31: "during pushing and

delivering the baby's head, some blood splashed over the doctor.

So, she got angry and said "what brings me here?"

what does she means by that? Why she is working in this area

if it cause her disgust ….."

3.1.2 Explain everything "I did

not have any choice in anything" "not enough information

was given to me":

A number of women expressed their satisfaction with the information

and explanation they received during their last birthing experience.

This was dominated by women who gave birth via caesarean section

because of its surgical requirements and by those who had

previous childbirth experiences.

P51: "as it was a caesarean

section I knew everything".

P173: " the best thing

was knowing the labour and birth stages".

A group of women from the three hospitals expressed their

needs for adequate ante-natal education and during birth explanations

to understand what would be done to them during labour and

birth and why.

P267: "I did not know what

was the injection given with I.V? Also what was the injection

given in my thigh?"

P12: "I did not have any

choice in everything, the midwife left me without dilatation

[episiotomy] till the baby came out without any assistance."

Moreover, women sought for more information during pregnancy

to correct any misconceptions about labour and birth and how

to take care of themselves and their babies after birth.

P273: "when the labour

pain started I had too much of (flower water + saffron) which

increased the pain with no cervical dilatation occurring.

I do not recommend taking anything without a doctor's prescription"

P193: "Not enough information

given to me about my stitches and how to take care of them."

P80: " "I refused

to take a deep breath during pushing because that will draw

the baby water…"

Some women needed more information about their childbirth

experience than others.

P80: "my daughter had the

umbilical cord tied around her neck and I think this is happened

because they did not let me push when I was ready to, is that

true?"

Another group of mothers questioned the presence and the role

of some maternity care providers who attended their labour

and birth.

P11: "I am a human, and

having student trainer during my birth increased my fears.

They should ask for my permission on that."

P309: "the worse thing

was having a male doctor and nurses in my birthing room while

no need for that."

A large number of women have not understood the breastfeeding

policies implemented across a number of the hospitals included

in this study. More antenatal education is required to adequately

prepare women for the change. The main area that women required

more education before the birth was the mechanism of the breastfeeding

and the reasons why breastfeeding was enforced immediately

following the birth.

P100 : "I do not know how

to breast feed my baby and know how to latch my baby to my

breast"

C 10: This woman's son was in

the nursery and she did not know what to do with the milk

accumulated in her breast.

3.1.3 To be good listener and trust

women's body "the best was listening to my fears and

calm me down":

Being cared by someone who listened to women's needs was a

significant factor in a good birthing experience for some

participants:

P279: "the best was the

doctor (F) and the nurse because they were the only two who

listened to my fears and calmed me down during the birth".

Women reported feelings of humiliation because no one listened

to them when they were in labour. For example several women

were very upset and described their experiences:

C31: "I was in pain and

I almost kissed their hands to check me up "sit down

just sit" they said. So I kept bothering them until they

examined me and they found that I was 8 cm dilated."

Then, P80 supports that:

P80: "I felt ready to push,

but the nurse stopped me from pushing and called me a liar.

Then someone came and examined me and saw my baby's head clear

just sitting there."

Another woman described her experience of medical errors as

a consequence of staff not listening to her.

P105: "The decision was

to do caesarean section and they start assessing my sensations

by pinching me and I told them that I felt that but the Dr.(M)

said to me 'you are joking' and I replied 'it is not the time

for jokes, I am in the O.R and I am between life and death'.

So they started cutting the incision and I felt the scalpel

and the stretching; and off course I screamed very loudly.

Then they said fine, fine and they gave me complete anaesthesia".

3.1.4 To provide safe care "I

felt safe because I was in caring hands"

Despite the fact that mothers believed that feeling safe during

labour and birth required a good relationship with the staff

and being informed of the progress, many women did not have

that experience. These women felt unsafe which lead them to

not have a pleasant childbirth experience.

P171: "the best thing was

I gave birth in this hospital which has better care and safety

for patients and informing patients about their rights".

C31: "They documented my

blood type as positive while I am negative, so when I asked

for the injection they told me I do not need it. So, I told

them I had an abortion before in this hospital and I had the

injection. Finally, they did blood test for me. To be honest,

I am very scared about my baby because of the wrong information

they have so they may give my baby the wrong treatment"

Feeling safe for many women was associated with receiving

kindness from their caregiver:

P204: "the best thing occurred

to me during my last birth was the treatment of the health

team with humanity. I felt safe in their hands".

P219: "I felt safe because

I was in caring hands. This was my best birth".

3.1.5 Caring and helpful staff "they

treated me as a princess"

Participating women reported their pleasant childbirth experience

when in the care of helpful, caring staff, and described how

this improved their psychological status and assisted in their

ability to cope with the difficulties of their births:

P120: "the best thing was

the help of the staff during labour and birth."

P134: "The midwife who

took care of me was better than the doctor (F) who I met.

Those midwives knew everything about my condition better than

the doctor herself and they treated it very well, my regards

to them."

Alternatively, one woman who reported receiving good care

also expressed her feelings when encountering uncaring staff.

3.1.6 I needed support and cooperation

"support during labour to relieve psychological stress"

Being cared by supportive cooperative staff was a primary

factor in the mothers' assessment of a better birthing experience:

P298: "the best thing was

the medical team continuous support till the birth complete"

P281: "the medical staff

team in the birthing room were very cooperative and understanding".

Many women reported looking for support and cooperation from

staff and not finding it:

P196: "I waited for 2-3

hours in the waiting area until I could not tolerate the pain

anymore and I was deteriorating physically and psychologically."

P279: "After all this I

have been left in the birthing room till 4 pm without food

or pain killer and with complete ignorance to all my calls

and no kindness".

Experiencing pain is the first characteristic for any birth

experience; a number of women reported their needs for staff

support and cooperation in order to gain control over pain.

P49: "one of the worse

things was the labour pain it was very intense, but it was

treated very well and I was satisfied"

P45: "the worse thing was

the pain and contraction without analgesics."

P12: "….I did not

have any pain relief or oxygen [nitrous oxide]".

Having an induction was not a pleasant experience for some

women and they took the time to express their feelings about

it.

P121: "the worse thing

was being induced in my first birthing experience but then

everything went good with staff help."

Having vaginal examination and episiotomy or stitches are

considered by most Saudi women as a sensitive uncomfortable

procedure and one that increases women's fears and anxiety.

P305: "they agonize us

with vaginal examination."

P146: "My birth was soft,

easy because I did not have any operation or episiotomy".

3.1.7 To provide the care with a positive

attitude "The staff treated us very badly, they have

bad attitude":

Many mothers described what they considered to be bad birth

experiences:

P195: "the worse things

were the nervousness of the nurses and doctor (F)".

P116: "the worse thing

was the treatment by the midwife or nurse. It was bad to the

extent that she told me if you have any problem go out of

the hospital".

C18: "the staff are treating

us very badly, they have a bad attitude"

The experience of being treated badly during labour and birth

affected women's ability to cope. Some women were unable to

overcome this experience:

C28: a woman said after a quiet

period "the doctor treated me badly and kept saying "come

on come on open your legs stop (Dalaa) [this word means acting

like a kid or speaking softly]".

P273: "Everyone I met treated

me with respect except the vaccination nurse, she had a very

bad manner and had religious racism and no kindness".

Several women who experienced staff with bad attitude reported

that this situation prevented them from speaking out for themselves

and their babies.

P89: "after she took the

baby from me she threw him on cot, he was hurt and cried and

I could not say anything because I was tired".

C12: this woman was very upset

because the nurse forced her to breastfeed her twin. "I

was scared and cried as the nurse pinched and hit my thigh

in a funny way to make me breastfeed but I did not like the

way the nurse treated me".

3.2 Hospital rules and policies and childbirth experience:

Childbirth experiences in Saudi Arabia are influenced by what

is offered and allowed in the hospital in which the woman

chooses to give birth. For example, having the husband or

family member attending the birth is not a choice offered

to women in some hospitals in Saudi Arabia. On the other hand,

establishing a new policy such as BFI (Breastfeeding initiation)

required better explanation to women in order to prevent any

misunderstanding or misinterpretation.

3.2.1 Family Company "I thank

everyone who assists in spreading this culture":

For some women having their husband or a family member during

labour and birth was an essential element to improving their

birthing experience.

P11: "the worse thing was

not allowing someone to stay with the patient [woman] although

this is the time when they are desperate to have someone with

them".

P84: "allow husbands of

women to attend the labour, and this should be optional".

P161: ":the best thing

happened during my birth experience and I thank everyone who

assists in spreading this concept which is allowing my husband

to be with me in birthing room, because him being beside me

helped me a lot and made my birth easier."

C24: "They did not allow

my mother until the doctor came and allowed her"

3.2.2 Breast feeding initiative BFI

policy "the worse thing was leaving the baby with the

mother all the time"

Participating women were not happy with the 'rooming in' policy

introduced by the hospital to support and encourage breastfeeding

(BFI). Women expressed their needs for family company during

their hospital stay to help them to take care of the baby.

P49: "I was not expecting

to care of my daughter because I was in a very bad condition,

I was not able to control myself how can I provide care to

my daughter".

P214: "the worse thing

was leaving the baby with the mother all the time, and not

helping the mother changing the baby, because the mother needs

someone to help".

C26: a primi (caesarean section)

woman was so confused and very overwhelmed….She said

"I am very depressed from the pregnancy and birth, I

need someone with me I am primi and gave birth caesarean section".

On the other side, women were unaware that this policy has

been done for a purpose and interpreted this as neglect on

the nurses' behalf. This issue caused an inconvenience for

the women and affected their birthing experiences.

C30: "the important thing

is their limited care to the baby".

P309: "…Also they

did not care of the baby after birth but leaving that to the

mother while she is tired"

P12: "…Nurses refuse

to provide mums with milk for babies although they knew there

is no milk still in their breasts."

P38: "Looking for the nursery

for healthy baby to take them from mothers after birth, so

she can rest for at least three hours".

4. Discussion

Women were willing to share their birth experiences and were

not hesitant to make the most of this opportunity to reflect

on what could be changed to improve experiences for other

women. The relationship between women and maternity care providers

was reported as the dominant factor that influences Saudi

mothers' satisfaction with the maternity care they received.

The most empowering experience for these women was to be cared

for by staff with a positive attitude, someone who provided

continuous support, who showed respect for the person and

who could be trusted to ensure their safety. This finding

has been supported by a number of studies which reported that

positive, trusting and cooperative relationships between women

and maternity care providers were the greatest influence in

women feeling empowered when giving birth (23). The pain associated

with labour and birth can be very difficult experiences for

women who are feeling vulnerable and unsafe. Women's ability

to manage pain during labour is negatively influenced when

feeling unsupported and unsafe (24, 25).

Women reported feeling dissatisfied with their birth experiences

as a result of lacking trust in the maternity care providers

who did not give them the respect they deserved. Respect was

not shown when staff did not provide them with necessary information

on their care and the reasons this care was required, and

or not listening to their needs or ignoring their distress.

This is evidenced when some participating women took the opportunity

to ask the researcher questions about their birth or the condition

of their baby. Educating women regarding what to expect during

pregnancy, labour, birth and breast feeding, and explaining

the role of each member of the maternity care team is a crucial

element in the development of a respectful trusting relationship

which in turn leads to safe maternity care. The need to be

able to trust maternity care providers is closely linked with

the degree of respect that was shown to women by the staff

(25-28).

Having family members to provide support during labour and

birth and post-natally is one of the choices available for

women in most maternity settings within developed countries.

The attendance of family during labour and birth choice was

incorporated into hospitals' policies because of its strong

relationship with the women feeling empowered, in control

of their birth and being more satisfied with their birth experience.

This positive relationship was evidenced by a number of studies

conducted worldwide (25, 27, 29). For Saudi women, it was

a different story as they reported their dissatisfaction and

loss of control as a result of not having the choice to have

a family member attending their labour and birth. Only 22%

of public hospitals in Jeddah one of the biggest cities in

KSA allow a companion to attend labour and birth (2). Nevertheless,

participating women highlighted their needs for family support

through labour and birth as this would help them feel safe,

satisfied and in control. Consequently, women must have the

choice to have a family member throughout their labour and

birth. To do so maternity policies in KSA required some modification

and updating according to women's preferences and latest evidence

regarding having family company during labour and birth.

Moreover, women misunderstood the application of the BFI ten

steps policy as recommended by WHO within public Saudi hospitals

(30). They interpreted the implementation of the policy as

maternity caregiver neglect and carelessness, which was accentuated

in women's words describing their experiences. Having their

babies with them 24 hours and the fact that there is no bottle

feeding provided to babies are the reasons causing women's

misinterpretation and dissatisfaction with birthing experiences.

Changing this policy is not the answer. However, women need

to be informed about this policy early during pregnancy, and

they must be educated why and how the application of this

policy is important (30). This information can be delivered

to pregnant women during antenatal education sessions, which

will prepare them to accept the care delivered to them later

and protect the staff from being misinterpreted.

This study is the first to explore women's birthing experiences

in public hospitals in Saudi Arabia. Women have highlighted

their needs for better, more satisfying birthing experiences.

The overarching need for all women is to be cared for by supportive

cooperative positive maternity care providers who deliver

safe birth care. In addition to the staff support, women were

looking for family support throughout labour and birth as

this is not currently an option for them in most public hospitals

in Saudi Arabia while it was one of the major women's claims.

Furthermore, women showed their demand for more information

about labour and birth, that could be fulfilled with frequent

accessible affordable antenatal educational classes. This

demand also requires continuous explanation and consultation

from the staff during labour and birth. This research sets

off the base for further research reporting Saudi women's

perspectives, voices and experiences regarding maternity care

they receive.

The limitation of this study is that the sample excludes women

who do not read or write Arabic. Also, while this study was

conducted within three large public maternity hospitals that

have high birth rate, this is limiting the representativeness

of the sample of the study.

Conclusion

Maternity care policy makers and maternity care providers

in Saudi Arabia have to consider empowering childbearing women

and ensuring safe motherhood. This can be accomplished by

reviewing and updating maternity policies with women's preferences

and latest up to date research evidence. This study provides

findings that focus on empowering women throughout labour

and birth with the staff and family support, adequate education

and explanation, and availability of choices. The main updates

that this study could add are introducing ante-natal educational

classes during pregnancy, explaining and consulting women

about everything.

Acknowledgements and Disclosures

The authors wish to acknowledge and thank every woman who

spent her time writing or conversing with researcher and sharing

her birthing experience.

References

1. Nigenda G, Langer A, Kuchaisit C, Romero M, Rojas G, Al-Osimy

M, et al. Womens' opinions on antenatal care in developing

countries: results of a study in Cuba, Thailand, Saudi Arabia

and Argentina. BMC Public Health. 2003;3:17.

2. Altaweli RF, McCourt C, Baron M. Childbirth care practices

in public sector facilities in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: A descriptive

study. Midwifery. 2014;30(7):899-909.

3. Anonymous. QLD:Maternity services review. Australian Nursing

Journal. 2004;12(3):8.

4. Bruinsma F, Brown S, Darcy M-A. Having a baby in Victoria

1989-2000: women's views of public and private models of care.

Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2003;27(1):20-6.

5. Brown S, Lumley J. Satisfaction with care in labor and

birth: A survey of 790 Australian women. Birth. 1994;21(1).

6. Bhattacharya S, Tucker J. Maternal Health Services. International

Encyclopedia of Public Health. 2008:210-21.

7. Newnham E. Midwifery directions: the Australian Maternity

services Review. Health Sociology Review. 2010;19(2):245-59.

8. Hundley V, Penney G, Fitzmaurice A, van Teijlingen E, Graham

W. A comparison of data obtained from service providers and

service users to assess the quality of maternity care. Midwifery.

2002;18(2):126-35.

9. Hundley V, Rennie AM, Fitzmaurice A, Graham W, van Teijlingen

E, Penney G. A national survey of women's views of their maternity

care in Scotland. Midwifery. 2000;16(4):303-13.

10. Mander R, Melender H-L. Choice in maternity: rhetoric,

reality and resistance. Midwifery. 2009;25(6):637-48.

11. Ny P, Plantin L, Karlsson ED, Dykes A. Middle Eastern

mothers in Sweden, their experiences of the maternal health

service and their partner's involvement. Reproductive Health.

2007;4(9).

12. Hildingsson I, Thomas JE. Women's perspectives on maternity

services in Sweden: processes, problems, and solutions. Journal

of Midwifery & Women's Health. 2007;52(2):126-33.

13. Miller AC, Shriver TE. Women's childbirth preferences

and practices in the United States. Social Science & Medicine.

2012;75(4):709-16.

14. Oweis A. Jordanian mother's report of their childbirth

experience: Findings from a questionnaire survey. International

Journal of Nursing Practice. 2009;15(6):525-33.

15. Mohammad KI, Alafi KK, Mohammad AI, Gamble J, Creedy D.

Jordanian women's dissatisfaction with childbirth care. International

Nursing Review. 2014;61(2):278-84.

16. Hatamleh R, Shaban IA, Homer C. Evaluating the Experience

of Jordanian Women With Maternity Care Services. Health Care

for Women International. 2012;34(6):499-512.

17. Guest M, Stamp G. South Australian rural women's views

of their pregnancy, birthing and postnatal care. Rural Remote

Health. 2009;9(3):1101.

18. Ministry of Health. Health statistics year book 1432/

2011. In: statistics Gao, editor. 2012.

19. Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and Conducting

Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication; 2007.

20. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in Psychology.

Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77-101.

21. Guba E, Lincoln Y. Fourth generation evaluation. London:

Sage; 1989.

22. Prion S, Adamson KA. Making Sense of Methods and Measurement:

Rigor in Qualitative Research. Clinical Simulation in Nursing.

2014;10(2):e107-e8.

23. Goodman P, Mackey M, Tavakoli A. Factors related to childbirth

satisfaction. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2004;46(2):212-9.

24. Hodnett ED. Pain and women's satisfaction with the experience

of childbirth: a systematic review. American Journal of Obstetrics

and Gynecology. 2002;186(5).

25. Fleming SEMNRNPCNS, Smart DD, Eide PP. Grand Multiparous

Women's Perceptions of Birthing, Nursing Care, and Childbirth

Technology. Journal of Perinatal Education Spring. 2011;20(2):108-17.

26. Goberna-Tricas J, Banus-Gimenez MR, Palacio-Tauste A.

Satisfaction with pregnancy and birth services: the quality

of maternity care services as experienced by women. Midwifery.

2011;27:e231-e7.

27. Corbett CAAMSNFNPc, Callister LCPRNF. Giving Birth: The

Voices of Women in Tamil Nadu, India. MCN, American Journal

of Maternal Child Nursing September/October. 2012;37(5):298-305.

28. Meyer S. Control in childbirth: a concept analysis and

synthesis Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2012;69(1):218-28.

29. Khresheh RRN, Barclay L. The lived experience of Jordanian

women who recieved family support during labor. The American

Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing. 2010;35(1):47-51.

30. Division of child health and development. Evidence for

the ten steps to successful breastfeeding: World Health Organization;

1998.

|

|