| |

August

2013 - Volume 7, Issue 4

Educating Nurses

for Person-Centered Care

|

( (

|

Lois Thornton

Correspondence:

Lois Thornton

University of Calgary, Qatar

P. O. Box 23133, Doha, Qatar

Telephone: 974 4406 5319

Fax: 974 4482 5608

Email: lethornt@ucalgary.edu.qa

|

|

|

Abstract

Background and Objectives: A person-centered

model for long-term institutional care of elder persons

is supportive of Arab societal values and Islamic beliefs.

Four workshops were conducted for nurse leaders from

long term care facilities in Qatar with the overall

objective of initiating a practice culture change which

would result in evidence of more person-centered care

practices.

Methods: Workshops were

held weekly for 4 weeks. Participants were 23 nurse

managers and supervisors from 3 long term residential

facilities in Doha, Qatar. Evaluation forms were completed

by participants after each workshop and a focus group

was conducted with the participants from one facility

12 weeks after the workshops.

Results: Participants

reported increased person-centered care practices on

their units. These practices began with staff coming

together around shared values and philosophy and included:

more attention to residents' personal preferences; inclusion

of residents and family in decision-making and social

activities; individualized care plans; therapeutic relationships.

Discussion: More research

into the implementation of care models that support

Arab religious and family values is essential to meet

the growing need for high quality long term residential

care in the Arab Gulf region.

Key Words: Person-centered

care, education, elders, Arab society

|

Introduction:

Long term institutionalized care for elderly persons is a

relatively new phenomenon in the Arab Gulf countries. However,

the Arab population, like the rest of the world, is aging

and the need for residential long term care for older people

is likely to increase. This need will be exacerbated by societal

and family changes related to modernization that will challenge

traditional expectations of the family to provide all care

for its aging members (1,2). At present, residential long

term care in the region tends to be clinically and task oriented

(3, 4). In most instances, care is provided by expatriate

nurses of diverse backgrounds and various levels of knowledge

of Arab culture and society. Models of care that support Arab

religious and family values are required for high quality

long term care alternatives for Arab families.

A person-centered model of care ensures the dignity of the

individual and encourages involvement of the family unit in

care, in keeping with Arab societal values and Islamic belief.

As well, a person-centered care framework could bring a diverse

nursing workforce together around a common philosophy and

consistent approach, leading to improved health outcomes and

satisfaction of residents and their families (5). Person-centeredness

is grounded in shared values and expressed through the workplace

culture of care.

This paper describes an educational program provided to nurse

leaders of long term care facilities in Qatar. Utilizing the

person-centered care framework developed by McCormack &

McCance (5), the intent of the program was to introduce nursing

leaders to the concepts of person-centered care, investigate

shared values that facilitate the development of a person-centered

workplace culture, and analyze how the shared values are operationalized

in practice. By directing the education to nursing leaders,

it was hoped that they would transfer their knowledge to front-line

staff, encourage action learning by staff and begin a culture

shift on their units.

Literature

Review

Nursing has long identified person-centeredness, holism and

individualized care as being integral to quality patient care.

However, within the past decade the international focus on

humanizing health and social services has precipitated extensive

research and literature on the meaning of the term "person-centered"

and its implications for nursing and other healthcare practice

(5). Person centered care has been defined as "an approach

to practice that is established through the formation and

fostering of therapeutic relationships between all care providers,

patients, and others significant to them" (6, p. 3) and

is based on the values of respect for persons, self determination,

mutual respect and understanding.

McCormack & McCance (5) purport that nurses often experience

person-centered "moments" in their practice, but

that sustained cultures of care where person-centeredness

is commonly recognized as the "way of doing business"

are infrequently encountered. Person-centered cultures of

practice are cultivated through a commitment to change and

careful attention to the care environment and care processes

as well as the attributes and skills of the nurses providing

care (5).

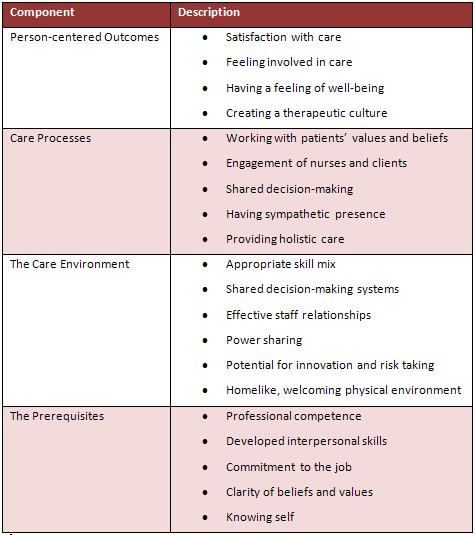

The framework developed by McCormack & McCance (5) places

person-centered outcomes at the center of a care environment

that is supportive of person-centered care processes and dependent

on the person-centered skills and attributes of the care givers.

The outcomes-satisfaction with care, involvement in care,

feeling of well-being, creation of a therapeutic culture-are

achieved only when there is synergy between the care processes,

the care environment and the attributes of the carers. Person-centered

processes describe the approaches taken in completing the

tasks of care: working with patients' beliefs and values;

shared decision making; engagement of nurse and client; having

sympathetic presence, and providing holistic care (5). The

processes can happen only in an environment that supports

shared decision-making, power sharing, and effective staff

relationships, that attends to appropriate skill mix and that

facilitates innovation and risk-taking. Both the care processes

and the care environment are made possible by the pre-requisite

attributes of the nurses: professional competence, developed

interpersonal skills, commitment to the job, clarity of beliefs

and values, and a good knowledge of self (5).

Components of the Person-Centered Nursing Framework

(5)

Procedure

The overall goal of the workshops was to begin a practice

culture change which would result in evidence of more person-centered

care practices. The objectives were (5):

• To promote an awareness and understanding of person-centered

nursing

• To articulate explicit values and beliefs that inform

the provision of nursing care

• To develop a shared vision that promotes person-centered

nursing practice

• To collect information on the quality of resident and

staff nurse experience in order to benchmark practice change

• To identify areas for practice change

The workshops were facilitated once a week over four consecutive

weeks. Participants included head nurses and nursing supervisors

of two long term care facilities and a newly opened community

care facility for assisted living. There were 23 participants

in all. Attendance at each workshop varied from 23 to 16.

A focus group was conducted with participants from one of

the long term care facilities 12 weeks later to evaluate the

outcomes in practice. Written consent was received from all

participants in the focus group.

Nurse leaders were targeted as participants with the expectation

that they would become facilitators of practice change on

their units. The workshops utilized creative ways of unleashing

the nurses' leadership potential. By co-creating a shared

vision for care, and critically reflecting on care practices,

they moved a step toward developing a culture of person-centered

care. During the final workshop, they agreed on one priority

area for change. They clearly identified the problem, and

brainstormed on an action plan for change. The nurses were

enabled to use the action learning cycle, to critically reflect

on their work and work environment and to develop alternative

ways of thinking and doing that would enhance quality of life

and satisfaction for residents and families.

The first workshop introduced the participants to the concept

of person-centeredness and the person-centered care framework.

An activity called "Victorian Parlour Game" (7)

was used to help participants recognize empathy for the residents

under their care. In this activity, participants were asked

to think about the question: "if I were one of my residents,

how would I feel right now?" The answers of all the participants

were then organized into an insightful poem that indicated

that each participant was aware of the feelings of isolation,

loneliness and hopelessness often felt by residents of elder

long term care. (See "In Long Term Care")

In small groups, participants mapped aspects of a case study

against the person-centered framework. After plenary discussion

of this activity, participants discussed in pairs how these

concepts could be used to change some practices on their units,

and decided on three ways that they could use these ideas

in their practice in the coming week.

In the second workshop, participants reflected on their individual

values and shared these with one other person in the group.

Then they worked with others from the same nursing unit to

agree on a common set of values and write a shared vision

of nursing care in their unit using the following headings:

• We believe the purpose of our nursing care is...

• We believe this purpose can be achieved by...

• The factors that will help us achieve this purpose

are...

• Other values and beliefs about nursing in our unit

are...

The groups then created a poster depicting their vision and

developed a plan for sharing this with their staff in the

coming week. As preparation for the next workshop, they were

asked to observe care on their unit in the coming week and

note one instance of care that was in keeping with the vision,

and one that did not fit with the vision.

During the third workshop participants evaluated the quality

of the patient-centered processes on their units by comparing

their observations of care with the vision that they had developed

and identifying sources of data for evaluating practice. Using

a provided set of questions to guide their reflection on each

of the person-centered processes, unit groups were asked to

evaluate the quality of care on their units. They then brainstormed

how they could validate these evaluations by using sources

of data available to them. Each group developed a plan for

evaluating the use of person-centered processes on their unit

and for identifying areas of practice that needed to change.

The final workshop examined the attributes of the nurse and

the care environment that are essential for a person-centered

culture of care. It also aimed to assist participants to plan

for a continuous trend toward a person-centered culture of

care. In their unit groups, participants evaluated the context

of care in their facility and discussed how the care environment

contributes to the areas of care that they had identified

for change. Plenary discussion identified and prioritized

common themes related to change to the care context.

The top priority theme was then analyzed by the group to clarify

the problem, identify the evidence of the problem, suggest

desired outcomes, develop possible solutions, and decide on

how outcomes could be evaluated. The action learning cycle

(plan, act, observe, reflect) was presented as a process for

ensuring continuous change in the care culture.

By engaging nursing leaders in reflecting on their practice

settings and comparing what they see with the visions that

they have developed, these workshops initiated a process of

change toward more person-centered

care. Identification of one priority area of change, and employment

of the action learning cycle created the opportunity for the

change process to be sustained.

Evaluation

An evaluation form was completed by participants at the end

of each workshop. Participants commented: "have started

(a change process) and will continue"; "very, very

much excited (to initiate a change in care practices)".

Responses to the evaluation questions indicated that participants

understood the concepts from the workshop, and were able to

identify significant sources of data for evaluating care practices

on their units. Many participants identified incongruence

between care being provided on the units and their shared

vision: "care is task centered" and "nurses

do not spend time talking with residents". They recognized

methods for gathering data on the care processes on their

units including: talk with the residents and let them tell

their stories; patient satisfaction survey; observation; asking

questions; random visits; interviews with the residents and

families; getting feedback from staff. The participants' high

level of engagement in the unit group work as well as the

plenary discussion indicated that the workshops were relevant

to them. They commented after each workshop that they had

enjoyed and learned from each session.

In order to evaluate the usefulness of the workshops in starting

a process of change, a focus group was conducted at one of

the participating long term care facilities 12 weeks after

the workshops were completed. The purpose was to ascertain

if indeed practice change had occurred that would provide

greater quality of life and satisfaction for residents and

families.

Focus group comments indicated that practice change related

to individualized care, inclusion of residents and families

in care decisions, and improved services to residents and

families had indeed occurred. Admission assessment forms had

been modified to include more information about residents'

likes and dislikes, preferred activities, hobbies, etc. and

individualized care plans were developed based on these preferences.

Copies of the care plans were shared with families as well

as the interdisciplinary team. Interests of family members

were being noted and families were included in activities

on the units. Recognizing the desire of one resident to be

involved in meal preparation, opportunities to help prepare

meals for her family were provided, and a weekly cooking activity

was made available to all residents.

A committee had been established to plan activities for residents

and more activities were offered in the afternoon and evening

to accommodate family participation. A volunteer visitor program

provided residents with greater variety in interaction as

well as companionship.

Nurses noted that residents were "more cheerful"

and more active participants in their care. One nurse commented

that resident/staff relationships were stronger. Nurses said

that family members, too, indicated that they appreciated

the extra attention.

Change did not come without some challenges. Nurses noted

that it had been difficult to readjust care routines to accommodate

resident preferences. There were on-going efforts to educate

all staff about the unit vision through making it visible

on posters throughout the facility and communicating it consistently

at monthly unit meetings. The vision had also been published

in both Arabic and English in the form of a handbook, an information

booklet and a poster at the bedside along with the resident

bill of rights.

Nurses also commented that the atmosphere at work had become

more positive and that staff felt informed and involved in

the changes being instituted. They felt that the challenge

now was to increase the momentum of the change and to gain

a reputation as a superior place to work.

Conclusion

Focus group comments indicated that a culture change was happening

in this long-term care facility and that resident care was

becoming more person-centered as outcomes of the workshops.

In this case, a work environment that allowed nurses the freedom

to create a unified vision for care and to recognize and change

practices that did not conform to the vision resulted in greater

satisfaction and quality of life for both nurses and residents.

This paper has described an educational program for nurse

leaders in long term care intended to generate a work culture

change to support the practice of person centered care. More

research into the implementation of care models that support

Arab religious and family values is essential to meet the

growing need for high quality long term residential care in

the Arab Gulf region.

|

In Long Term Care

Longing for compassion and loving care

For feelings of belonging

And the hugs and kisses that is sweet

Lonely and useless

Frustrated and sometimes afraid

They pity me

Such boredom, sadness and loneliness

But even though I am sick I am in safe hands

Anxious but

If my parents are around, beautiful the life is

Need for much attention and love

The time is too long: nothing to do

Bored and depressed

Rejected, alone, pitiful, powerless, depressed

I want to be with my family right now

The touch of their caress, the smile on their faces

Their voice saying how much they love me

Repulsed by wound exudates and smell

Pain but

Life here is better than at my house

Cannot express my feelings

Useless, wasted, a burden to society

They deal with me as an object not

A human being

Machine centered care

Upset and irritable

Lonely and irritable

Thank God for what and who I am

I will overcome and use the best of my abilities

To survive.

|

References

1. El-Haddad, Y. Major trends affecting families in the Gulf

countries 2003. http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/family/Publications/mtelhaddad.pdf

2. Sinunu M., Yount K., El Afify N. Informal and formal long-term

care for frail older adults in

Cairo, Egypt: Family caregiving decisions in a context of

social change. J Cross Cult Gerontol 2009; 24: 63-76.

3. Margolis S, Reed, R. Institutionalized older adults in

a health district in the United Arab Emirates: Health status

and utilization rate. Gerontology 2001; 47: 161-167.

4. Al-Shammari S, Felemban F, Jarallah J, El-Shabrawy A, Al-Bilali

S, Hamad J. Culturally acceptable health care services for

Saudi's elderly population: the decision-makers perception.

Int J Health Plan Manage 1995; 10: 129-138.

5. McCormack B, McCance T. Person-centered nursing: Theory

and practice. Oxford, U. K.: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

6. McCormack B, Dewing J, McCance T. Developing person-centered

care: Addressing contextual challenges through practice development.

Online J Issues in Nursing 2011;16(2):1-

7. Nisker, J. Narrative ethics in health care. In Storch J,

Rodney P, Starzonski R. eds. Toward a moral horizon: Nursing

ethics for leadership and practice. Toronto: Prentice-Hall;

2004.

|

|