| |

November

2014

- Volume 8, Issue 4

Moving

toward Integration: Group Dance/movement therapy with children

in Anger and Anxiety

|

( (

|

Anahita Khodabakhshi Koolaee

(1)

Mehrnoosh Sabzian (2)

Davood Tagvaee (3)

(1) Department of counseling,

Islamic Azad university,

Science and Research branch of Arak, Arak, Iran

(2) Department of psychology, Islamic Azad university,

Science and Research branch of Arak, Arak, Iran

(3) Department of psychology, Islamic Azad university,

Science and Research branch of Arak, Arak, Iran

Correspondence:

Anahita Khodabakhshi Koolaee

Department of counseling,

Islamic Azad university,

Science and Research branch of Arak, Arak, Iran

Email: anna_khodabakhshi@yahoo.com

|

|

|

Abstract

Background: Dance/ movement therapy (DMT) is

defined as the "psychotherapeutic use of movement

as a process that furthers the individual's emotional,

cognitive, social, and physical integration'. DMT can

elicit positive change, growth, and health among adults

and children.

Objective: The purpose of this study was to examine

the effect of Dance/Movement Therapy (DMT) in decreasing

levels of aggression and anxiety among children ages

6-7 years old enrolled at four private pre-school centers

in Tehran, Iran in 2013.

Method: The design of this study was Quasi-experimental

pre-post test with control group. Thirty children were

selected by random method from four private pre-schools

in Tehran. Then, 15 children were randomly assigned

to the experimental group and 15 other children were

elected for the control group. The dependent variables,

aggression, and anxiety were measured twice throughout

the 10-week study. Ten one-hour group DMT sessions were

given as the interventions for the experimental group.

For gathering data we used Children's Inventory of Anger

(ChIA) and Spence Children's Anxiety Scale (SCAS). Data

was analyzed by Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA).

Results: There was a significant difference in

aggression and anxiety scores between the two groups

of participants. The experimental group showed lower

incidence aggression and anxiety after DMT intervention.

Conclusion: The findings of this research suggest

DMT can be beneficial for all children with Anger and

Anxiety. In addition, DMT can provide a sense of safety,

self-awareness, other or people mindfulness, and mental

health for children.

Key words: Dance/movement Therapy (DMT), Aggression,

Anxiety, Pre-school children

|

Background

The American Dance Therapy Association defines dance/movement

therapy as the "psychotherapeutic use of movement to

further the emotional, cognitive, physical, and social integration

of the individual" (1). American Dance Movement therapy

points out the benefits of DMT as "There is a variety

of goals and techniques and activities used in individual

and group DMT sessions, including; movement behavior, Expressive,

communicative, and adaptive behaviors are all considered for

group and individual treatment. Body movement, as the core

component of dance, simultaneously provides the means of assessment

and the mode of intervention for dance/movement therapy. DMT

is useful for mental health, rehabilitation, medical, educational,

and forensic settings, and in nursing homes, day care centers,

disease prevention, health promotion programs and in private

practice. DMT is effective for individuals with developmental,

medical, social, physical, and psychological impairments.

In addition, DMT is used with people of all ages, races, and

ethnic backgrounds in individual, couples, family, and group

therapy formats"(1). Schmais (1985) looked at factors

within group dance/movement therapy that elicit positive change,

growth, and health in its participants. Factors that can be

seen in typical group dance therapy sessions include synchrony,

expression, rhythm, vitalization, integration, group cohesion,

education, and symbolism (2). There have been bodies of researches

done to examine the effects of Dance/ Movement therapy for

children. For example, Leventhal discussed DMT for the special

needs child. DMT could be beneficial indirectly for Special

children and create a new chance for them to learn new skills

and modify their patterned behaviors (3). In addition, Shennum

(1987) found out that the children who received DMT sessions

had lower levels of emotional unresponsiveness and negative

acting out (4). Throughout the literature review there have

been implications that Dance/Movement Therapy (DMT) has an

impact on mental health of children who present with various

issues, including severe trauma (5), depression, attention

deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD), conduct disorder, as

well as psychosis, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress resulting

from physical and sexual abuse (6 & 7). DMT was also found

to have impact on children in struggle with communication

and motor skills ( 8), victims and children who were soldiers

and torture survivors (9 & 10). DMT education for clinical

staff examined by Lundy & McGuffin (11) has been shown

to have a positive effect on therapeutic holding with children

in an in-patient setting. Capello argues the effect of dance/movement

therapy in reviews of cross-cultural study by literature;

the literature implies it has influenced children's development

issues surrounding differences in child rearing and children

who have been survivors of war and torture (12).

Dance/Movement Therapy has been used as a tool to address

aggression and empathy; the curriculums have been utilized

in public schools as a preventative measure (13 & 14),

in a multi-cultural school setting (15), and in a residential

treatment program for emotionally and behaviorally disturbed

children with histories of abuse and/or neglect (4).

In some countries around the world, dance/movement therapy

brings a new opportunity for therapeutic and education methods

for clinicians and staff (Capello, 2008). In Iran Dance/Movement

Therapy is not approved as a formal therapeutic adjunct or

the curriculum in school settings. While, in Iran some private

pre-schools are using DMT for helping children with hyperactive

behaviors.

Objective

In this study, we examine the effect of Dance/ Movement Therapy

(DMT) as a new adjunctive therapy to help children with aggression

and anxiety in Tehran in2013.

Method

1. Participants and plan:

The design of this study was Quasi-experimental pre-post test

with control group. Thirty (6-7years old) children were selected

by random method from four private pre-schools in Tehran by

2013. Then, 15 children were randomly assigned to the experimental

group and 15 children were elected for the control group.

The dependent variables, aggression, and anxiety were measured

twice throughout the 10-week study. Ten one-hour group DMT

sessions were given as the interventions to the experimental

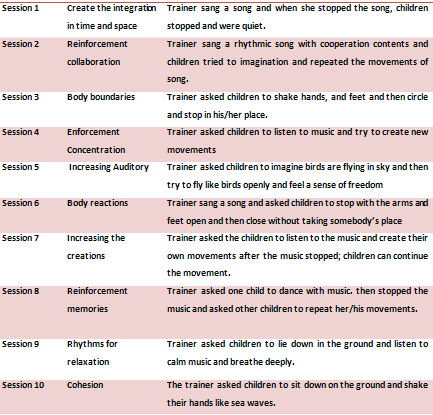

group. The DMT sessions were described in Table 1.

Table 1: Dance/movement therapy sessions

• Trainer ended every session with snacks and talking

about the session.

• All sessions were performed by Dance/Movement trainer.

For Children to be eligible for this study they must

1) Have been between the ages of 6-7 years old

2) Have been identified by their primary therapist

to address continuous serious aggressive behaviors and anxiety

3) They have not suffered severe physical disability

4) Carry a diagnosis of at least one of the following:

Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD), Oppositional

Defiant Disorder (ODD), Anxiety Disorder, or Learning Disorder

NOS

5) They have normal IQ

6) Be assigned to the identified pre-school centers

in Tehran

Subject Exclusion Criteria

Children may not be enrolled in this study if they

1) Were not enrolled at the identified pre-schools

2) Were not assigned to the designated classroom

3) Were younger than 6 years old or older than 7 years

old at any time from the onset of the study to the end of

data collection.

4) Carried a diagnosis on the Autism spectrum, Pervasive

Developmental Disorder (Asperger's Syndrome, Childhood Disintegrative

Disorder, or Rett's Syndrome), or Mental Retardation may not

participate in the study.

5) They suffered severe physical disability.

2. Measurement:

Participants responded to two questionnaires including; Children's

Inventory of Anger (ChIA), and Spence Children Anxiety Scale

(SCAS).

Children Inventory of Anger (ChIA):

The Children's Inventory of Anger is a 40-item child self-report

rated from 1 (no anger) to 4 (extreme anger) for children

6-16 years old. This questionnaire made by Nelson and Finch

(1993) and was reviewed in 2000. Children are asked to evaluate

their response to potentially provoking events (e.g, ''someone

cuts in front of you in a lunch line''). Although the Children's

Inventory of Anger has not been used in studies of parent

management training, it has demonstrated sensitivity to change

in psychosocial interventions with children (Nelson and finch,

2000). The ChIA includes subtests and scores in the following

areas: Frustration, Physical Aggression, Peer Relationships,

Authority Relations, and Inconsistent Responding Validity

Index. The test-retest reliability was Pearson's product-moment

correlation coefficient (r= 0.63 to 0.90) and internal consistency

was good (a = 0.96) (16). Validity

for the measure is supported in its correlation with peer

ratings of anger (17).

In Iran Children Inventory of Anger was translated to Persian

by researchers in this study and the test-retest reliability

was Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficient (r= 0.65

to 0.75) and internal consistency was good (a

= 0.86).

Spence Children's Anxiety Scale

(SCAS):

The Spence Children's Anxiety Scale created by Spence

(1998) is a self-report measure of Anxiety originally developed

to examine anxiety symptoms in children aged 8-12 years. The

SCAS consists of 44 items, 38 of which assess specific anxiety

symptoms relating to six sub-scales, namely social phobia,

separation anxiety, panic attack/agoraphobia, obsessive-compulsive

disorder, generalized anxiety and physical injury fears. The

remaining six items serve as positive ''filler items'' in

an effort to reduce negative response bias. Respondents are

asked to indicate frequency with which each symptom occurs

on a four-point scale ranging from Never (scored 0) to Always

(scored 3). A total SCAS score was obtained by Sum scores

of the 38-anxiety symptom items. Previous studies have demonstrated

high internal consistency, high concurrent validity with other

measures of child and adolescent anxiety, and adequate test-retest

reliability for total score (r= 0.92)(18). In Iran SCAS was

translated to Persian by Mosavi et al (2007) with adequate

test-retest reliability for total score (r= 0.89) (19).

3. Procedure, statistical methods,

and code of ethics:

Participants answered all of the questionnaires independently

under supervision of interviewers and parents filled out with

informed consent.

When participants were selected, researchers were told the

aim of the study to children and their parents and asked the

children to answer the questionnaires. For filling out the

questionnaire, reviewers read the questions one by one and

marked the questionnaire, because children could read and

write independently.

The data gathered from research was analyzed by Descriptive

statistical methods including; Mean, Standard deviation, and

percent frequency. In addition, inferential statistical methods

like, Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) implemented for research.

Data was analyzed by SPSS statistical package version 18.

Results

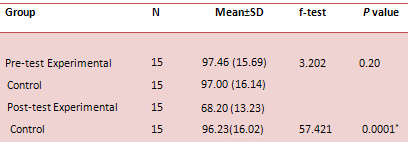

Table 2, shows the difference between mean score of Children

Inventory of Anger (ChIA) overall score in the two groups

with ANCOVA. Results of the Children Inventory of Anger (ChIA)

is shown in Table 2. Dance / Movement Therapy (DMT) intervention

in the treatment group decreased the level of Anger (68.20

± 13.23 vs. 96.23 ±16.02; p=0.0001).

Table 2: Differences between mean score of Children Inventory

of Anger (ChIA) overall score in the two groups with ANCOVA

Abbreviations: SD, Standard Deviation; f, F-test

The

results showed no significant differences between the mean

ChIA in pre-test scores. Rather, differences in the mean scores

of the ChIA in the two groups were significant after intervention

(p=0.0001), as confirmed by ANCOVA (p=0.0001; Table 2).

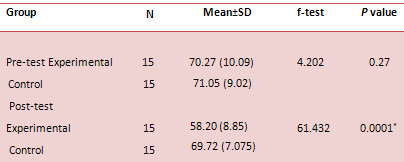

Results of the Spence Children Anxiety Scale (SCAC) presented

in Table 3. Dance / Movement Therapy (DMT) intervention in

the treatment group decreased the level of Anxiety (58.20

± 8.58 vs. 69 .72± 7.075; p=0.0001).

Table 3: Differences between mean score of Spence Children

Anxiety Scale (SCAS) overall score in the two groups with

ANCOVA

Discussion

The present research shows that Dance/Movement Therapy has

a beneficial effect in children with Anger and Anxiety. The

DMT sessions can reduce the levels of aggression among pre-school

children. This result was consistent with the previous study,

as an example; Lanzillo (14) found that DMT decreased the

level of aggression and increased the empathy in children.

In addition, Lanzillo cited that DMT could be used as curriculum

in schools to improve the social skills and empathy in children

and prevented behavioral problems in children. Furthermore,

Hervey and Kornblum (13) implemented the mixed-method of Dance/

Movement therapy for children at-risk. Results showed that

behavioral problems had dramatically reduced in children.

In addition, in 2004, Koshland and Wittaker evaluated the

peace through the Dance/ Movement therapy (DMT) program, created

by Lynn Koshland. The program was designed for violence prevention

with multi-cultural elementary school students. The results

revealed that the levels of aggression, and disruptive behaviors

had decreased, while, self-control among children who received

the DMT intervention had improved (15).

Caf, Krofic & Tacing (1997) examined the use of creative

movement and dance on children with struggles with communication

and self- awareness and expression of their feelings. They

found that the movement and dance could be helpful for children

participating in the research. Teachers reported that children

became more expressive of their feelings and more active (8).

There are several activities and modules applied in individual

and group Dance/movement therapy (DMT) sessions, including

Role-playing, the use of imaginative play, and structured

and non-structured movements (14).

As Leventhal (1980) noted Dance/ Movement Therapy (DMT) can

indirectly teach. The Children are participating in DMT activities;

they are more receptive to learning new skills and changed

their behaviors (3).

In conclusion DMT sessions can be beneficial for all ages

from children to aged people. DMT can improve positive coping

skills, impulse control, and self- esteem; bring social support

and interactions, self-awareness, improve body language, body

boundaries, in addition, to building empathy and ability to

form healthy relationships with others (14). DMT is used in

Iran as an informal program in pre-schools but researchers

suggest that DMT and Rhythmic Movements can be seen as a new

curriculum program for creating a new chance for children

to explore their own life through movements.

References

1- American Dance Therapy Association (ADTA) (2014). What

is Dance/ Movement Therapy? Retrieved July 2014 from www.ADTA.org/

About_DMT

2- Schmais, C. Healing processes in group dance therapy. American

Journal of Dance Therapy, 1985, 8(1), 17-36.

3- Leventhal, M. B. (Ed). Movement and growth: dance therapy

for the special child. 1980, New York : Center for Educational

Research.

4- Shennum, W. A. Expressive activity therapy in residential

treatment: Effects on children's behavior in the treatment

milieu. Child & Youth Care Quarterly, 1987, 16(2), 81-90.

5- Hervey, L., & Kornblum, R. An evaluation of Kornblum's

body-based violence prevention curriculum for children. The

Arts in Psychotherapy,2006, 33(2), 113-129.

6- Erfer, T., & Ziv, A. Moving toward cohesion: Group

dance/movement therapy with children in psychiatry. The Arts

in Psychotherapy, 2006, 33(3), 238-246.

7- Gronlund, E, Renck, B. & Weibull, J. Dance/movement

therapy as an alternative treatment for young boys diagnosed

as ADHD: A pilot study. American Journal of Dance Therapy,

2005, 27(2), 63-85.

8- Caf, B., Krofkic, B, & Tancig, S. Activation of hypoactive

children with creative movement and dance in primary school.

The Arts in Psychotherapy, 1997,24,(4), 355-365.

9- Harris, D.A. Pathways to embodied empathy and reconciliation

after atrocity: Former boy soldiers in a dance/movement therapy

group in Sierra Leone, Intervention, 2007, Vol 5, Nu: 3, 203-231.

10-Harris, D.A. Dance/movement therapy approaches to fostering

resilience and recovery among African adolescent torture survivors,

Torture,2007, Vol 17, Nu: 2, 134-155.

11- Lundy, H., & McGuffin, P. Using dance/movement therapy

to augment the effectiveness of therapeutic holding with children.

Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing,2005,

18(3), 135-145.

12- Capello, P. Dance/movement therapy with children throughout

the world. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 2008, 30(1),

24-36.

13- Hervey, L., & Kornblum, R. An evaluation of Kornblum's

body-based violence prevention curriculum for children. The

Arts in Psychotherapy,2006, 33(2), 113-129.

14-Lanzillo, A, A. The Effect of Dance/Movement Therapy on

Incidences of Aggression and Levels of Empathy in a Private

School for Children with Emotional and Behavioral Problems,

Unpublished Master of Arts Thesis, 2009, MA in Dance/ Movement

therapy, Drexel University, Philadelphia, USA.

15- Koshland, L., & Wittaker, J. W. B. PEACE through Dance/Movement:

Evaluating a violence prevention program. American Journal

of Dance Therapy,2004, 26(2), 69-90.

16-13- Finch AJ, Saylor CF, Nelson III WM. Assessment of anger

in children. In: Prinz RJ, editor. Advances in behavioral

assessment of children and families. Volume 3. Greenwich:

JAI Press; 1987. p 235-65.

17-Finch AJ, Eastman ES. A multimethod approach to measuring

anger in children. Journal of Psychology, 1983;115:55-60.

18- Spence, S. A measure of anxiety symptoms among children.

Behavior, research and therapy, 1998, 36(5), 545-566.

19- MoSavi, R, Moradi, A.R., Farzad, V., Mahdavi Harsini,

E, Spence, S.H. Psychometric Properties of the Spence Children's

Anxiety Scale with an Iranian Sample, 2007, www.SCASwebsite.com

|

|